As if a total solar eclipse across much of the US wasn’t enough of a spectacle for us, the Moon has another treat in store this April: a stunning earthshine. Peer up at our celestial neighbour over the next couple of nights and you should see a subtle, ghostly glow appearing on its surface.

Sometimes known as ‘the ashen glow’, ‘the old Moon in the new Moon’s arms’ or ‘the da Vinci Glow’, earthshine has been mesmerising onlookers for millennia, and now is the best time of year to catch a glimpse of the event.

When can I see Earthshine?

Weather permitting, you can see Earthshine this evening, Wednesday 10 April, just after sunset (7:56pm BST in London, 7:31pm EDT in New York City, 7:21pm PDT in Los Angeles).

If you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, then the earthshine should be particularly prominent over the next couple of nights. That’s because we’ve just had a new Moon, which is where the Moon is positioned in between the Earth and the Sun (hence, the eclipse).

Just after a new Moon, the only bit illuminated by the Sun is a small crescent (or waxing crescent, to be precise), and the earthshine effect becomes visible.

This is partly because the dim earthshine has less bright sunlight to compete with when only a small crescent is illuminated, but also because when the Moon is a sliver in our sky, the Earth is almost fully illuminated from the Moon’s perspective – think of it like a ‘Full Earth’ if you’re on the Moon.

Here’s how the Moon is shaping up over the next few nights:

- 10 April: 4 per cent waxing crescent Moon

- 11 April: 10 per cent waxing crescent Moon

- 12 April: 18 per cent waxing crescent Moon

So long as the skies remain clear, the earthshine effect should be visible on all of these evenings. Just after sunset is usually the best time to spot it.

But, if you don’t manage to catch a glimpse this time around, next month’s new Moon on 8 May will also be prime viewing time.

Read more:

- New Moon 2024: When is the next new Moon?

- Solar eclipse: The 20 best photos from 2024’s celestial spectacle

- 20 of the most amazing moons in the Solar System

What exactly is Earthshine?

Earthshine is the faint glow on the unlit side of the Moon visible during certain phases. Think of it like sunlight that’s taken a scenic detour:

- Sunlight beams hit Earth's surface, reflecting off our oceans, landmasses, and clouds.

- Some of this reflected light bounces back out into space.

- A portion of that Earth-reflected light reaches the Moon, illuminating the side facing us that isn't getting any direct sunlight.

Since this light has travelled a long way (Earth, then the Moon, then back to us), it's much dimmer than the part of the Moon directly lit by the Sun. This creates the soft, ethereal glow we call Earthshine.

undefined

Why is this the best time of year to view Earthshine?

Earthshine is more visible during the spring months (ie, right now if you’re in the Northern Hemisphere) because the Sun is more reflective then.

"The reflectivity of the Earth – its albedo – changes throughout the year. Snow and ice reflect lots of sunlight, but not so much light is reflected by land, and the vegetation on it. Our oceans are even less reflective, as water is so transparent," Dr Darren Baskill tells BBC Science Focus.

In the spring, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted towards the Sun after a winter pointing away from it, and leftover winter snow and ice in high-latitude regions reflect a lot of sunlight back out into space. This reflected light hits the Earth's side of the Moon, illuminating the dark portion with earthshine.

Since there's more reflective surface in the spring, earthshine is about 10% brighter than average during this time.

"In addition, the 'young' crescent Moon is higher in the sky as spring turns into summer, which also makes the phenomena easier to observe," Baskill adds.

What’s da Vinci got to do with it?

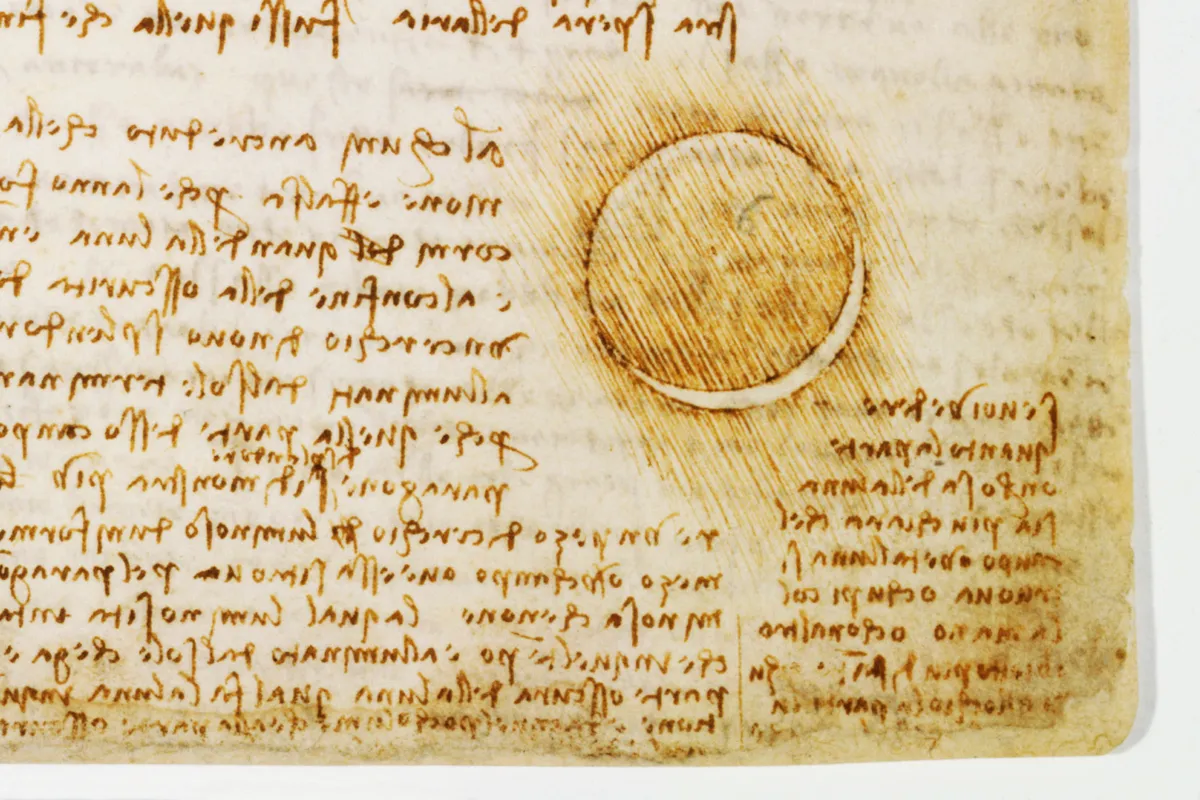

As if painting the Mona Lisa, Last Supper and Vitruvian Man weren’t enough, Leonardo da Vinci also had a crack at science during his lifetime. He was one of the first people to correctly explain earthshine and hence got to lend his name to the phenomenon often referred to as ‘the da Vinci Glow’ (he didn’t coin the term himself, thankfully).

Da Vinci made detailed sketches of the Moon as well as other celestial bodies and correctly identified that Earthshine was probably coming from sunlight reflected off Earth.

But before you feel totally inferior, he wasn’t spot on with his theory. He thought the effect came mostly from the oceans, rather than the all-important winter snow and ice.

What affects Earthshine?

As mentioned before, the earthshine is enhanced by the presence of snow and ice, but there are other factors affecting how bright the phenomenon appears too.

The big one is cloud cover since clouds can be both reflective and absorbent. Thick, white clouds reflect sunlight well, contributing to earthshine. Generally, the cloudier the Earth, the brighter the Earthshine, provided we can still see the Moon, of course.

In 2017, scientists revealed that the Earth’s albedo has been decreasing over the past couple of decades, meaning Earthshine is becoming less visible. This could be a sign that global warming is intensifying, as more heat gets absorbed by the seas and skies and less is reflected back into space.

Other factors that could affect how bright the Earthshine is include levels of pollution in the atmosphere and land-ocean distribution in a given hemisphere.

What equipment do I need to see Earthshine?

In short, not a lot. A pair of eyes should do the trick.

If you want to enhance the viewing experience, a pair of binoculars will help you pick out otherwise hidden details on the lunar surface.

About our expert

Dr Darren Baskill is an outreach officer and lecturer in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Sussex. He previously lectured at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, where he also initiated the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition.

Read more: