The sound of screeching tyres followed by a bus hurtling directly towards you. It’s not exactly something you’d want to come across when cycling up a steep, narrow road.

But in March 2015, on Franschhoek Mountain Pass in South Africa, that’s just what one cyclist was faced with after a bus driver swerved in an attempt to avoid two other cyclists while negotiating a sharp corner. The bus overturned and three passengers lost their lives.

In the investigation that followed, the police talked of prosecuting the bus driver for ‘culpable homicide’, a charge resulting from the negligent killing of a person according to South African law. But what might they have said if the bus had been driven by autonomous software?

Read more about driverless cars:

- What you need to know before getting into a driverless car

- Would it be possible for driverless cars to use echolocation?

- How will driverless cars avoid potholes?

- 5G: Driverless cars could warn each other of dangers using new network

The driver was faced with a rare and complicated type of moral dilemma in which they were forced to choose between two bad options.

Analysis of the above scenario raises two main questions: the first is to ask whether the accident could have been avoided by better vehicle maintenance, more careful driving, better road design or other practical measures and whether there was negligence in any of these areas.

The second is to ask that if the accident was not avoidable, then what was the least morally bad action?

When thinking about these issues in terms of driverless vehicles, the first question is relatively easy to answer. Driver software will have faster reaction times and be more cautious and physics-faithful than human drivers, meaning driverless cars will be able to stop extremely quickly once they detect a hazard. Also, they will never show off or get drunk.

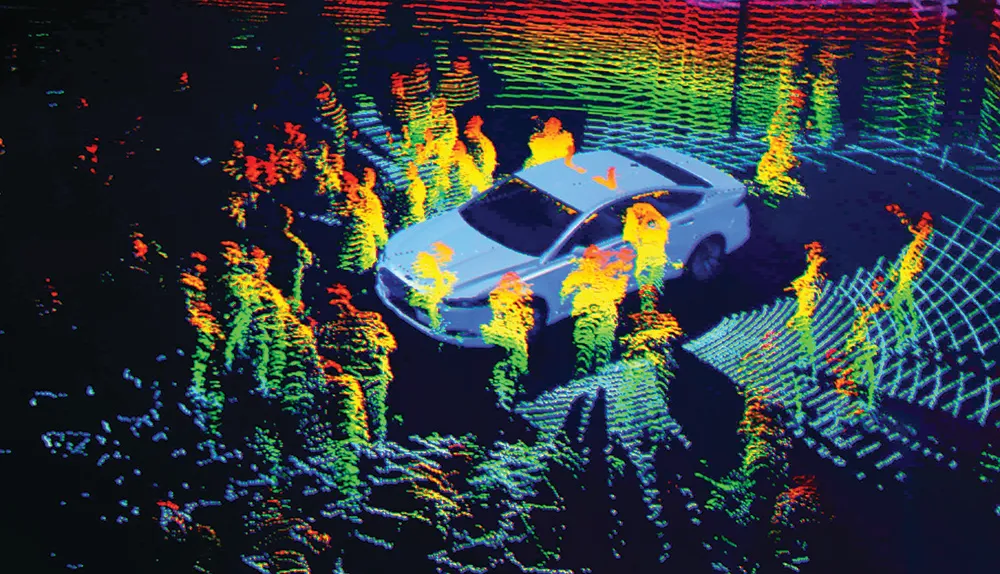

However, their sensors and image classification processes will remain cruder than human perception for some time to come, meaning they may not recognise or classify unexpected hazards the way humans do.

They won’t be able to reliably tell the difference between children and adults, for example. Nor will they know whether other vehicles are empty or are carrying passengers. Some commentators believe that once the technology is perfected, autonomous vehicles could provide us with a completely accident-free means of transport.

Yet large-scale statistical analyses, such as those carried out by Noah Goodall at the Virginia Department of Transportation, indicate that this is unlikely. Thanks to the existence of pedestrians, cyclists, and even animals, our roads are too unpredictable for any autonomous system to take everything into account.

So how do autonomous cars fit in with the moral question?

Firstly, autonomous vehicle driver software won’t have had years of real-life experience to learn the nuances of morality through praise, blame and punishment the way a human driver has.

Nor will it be able to use its imagination to build on these previous learning experiences. Imagine a similar situation to the above scenario.

A vehicle being driven completely by software and carrying one passenger is travelling uphill around a steep corner on a narrow two-lane mountain road.

Two children are riding bicycles down towards it on the wrong side of the road and a heavy truck is approaching in the other lane. To avoid the children, the car can head for the truck or drive off the side of the road, but if it stops the children will hit it.

Driving into the truck or off the precipice will likely kill the human passenger but save the children. Attempting to stop could lead to the children being killed if they crash into the car, yet the passenger will be protected. What should the car’s software be designed to do?

Built-in moral compass

Of course, such dilemmas are rare occurrences but they are nevertheless of key concern to engineers and regulators. But whereas the human bus driver mentioned above had only a frightening fraction of a second to make a life and death decision, the engineers have hours and hours in the safety of an office to design how the vehicle’s driver software will react.

Of course, this means that they cannot claim that they reacted ‘instinctively’ due to time pressure or fear. In the event of an accident, courts will say that the engineers have programmed the software rationally and deliberately and thus expect them to be fully morally responsible for their choices. So what must they consider?

There are three broad schools of thought.

One: autonomous driver software may be expected to operate to a higher moral standard than a human driver because of the lack of time pressures and emotional disturbances and its greater processing power.

Two: it could be expected to operate to a lower moral standard due to the sensors’ lack of classificatory subtlety and the overriding belief that only humans can act ethically because software cannot be conscious or feel pain.

Three: software may be expected to operate to the same moral standard as applies to human drivers.

Read more about cars:

- Plug-in hybrid cars: Are they really the eco-friendly choice?

- Why do blackbirds always dive in front of my car?

All three options imply that the moral standard expected of human drivers in such dilemmas is definitively known. But when forced to act quickly, humans will often use their instincts rather than conscious, rational analysis.

Instincts may be honed through life experience or deliberate practice but they are not under conscious control at the point of application.

Our emotions can also influence instinctive action. So a human driver might instinctively flinch away from a large object like the truck, without being able to process the presence of the cyclists. Or, a human with different instincts might act to protect the vulnerable children without recognising their own danger.

Such unconsidered reactions are hardly moral decisions that are worthy of praise or blame. So what would moral behaviour require if we set aside the confounding factors of time and emotion?

The study of such questions takes us into the territory of ethical theory, a branch of philosophy concerned with extracting and codifying the morally preferable options from the morass of human behaviour and beliefs. Philosophers have developed logically consistent theories about what the morally preferred actions are in any given situation.

Today, two main contenders exist for the top theoretical approach: consequentialism and deontology. Consequentialist theories say the right action is that which creates the best results. Deontological theories say the correct action is that in which the people’s intentions were best, whatever the results.

Despite starting with different founding assumptions about what is valuable or good, these two theories agree on the morally preferable action in the majority of common situations. Nevertheless, they do sometimes differ.

Algorithm ethics

Both consequentialism and deontology are based on consistent reasoning taken from a small set of assumptions, which is something algorithms can do.

So, can we write algorithms that will calculate the best course of action to take when faced with a moral dilemma? Those working in the small scientific field of machine ethics believe that we can.

Artificial intelligence researchers Luis Moniz Pereira and Ari Saptawijaya have been collating, developing and applying programming languages and logic structures that capture deontological or consequentialist reasoning about particular moral problems.

These programs are limited in scope, but their work suggests that it would be possible to program an entity to behave in accordance with one or other of the major ethical theories, over a small domain.

This work is often criticised, not least for not covering the entire range of ethical problems. But a slightly deeper look at moral theory suggests that’s inevitable.

Most cases where the two moral theories agree are easy for courts of law to decide. But there are certain types of cases in which judges must call on the wisdom drawn from years of courtroom experience.

Examples include trials for war crimes, shipwreck and survival cases, medical law, and also road accidents. Because of their complexity and the moral discomfort they cause, cases such as these attract lots of legal and philosophical attention.

Trolley problems

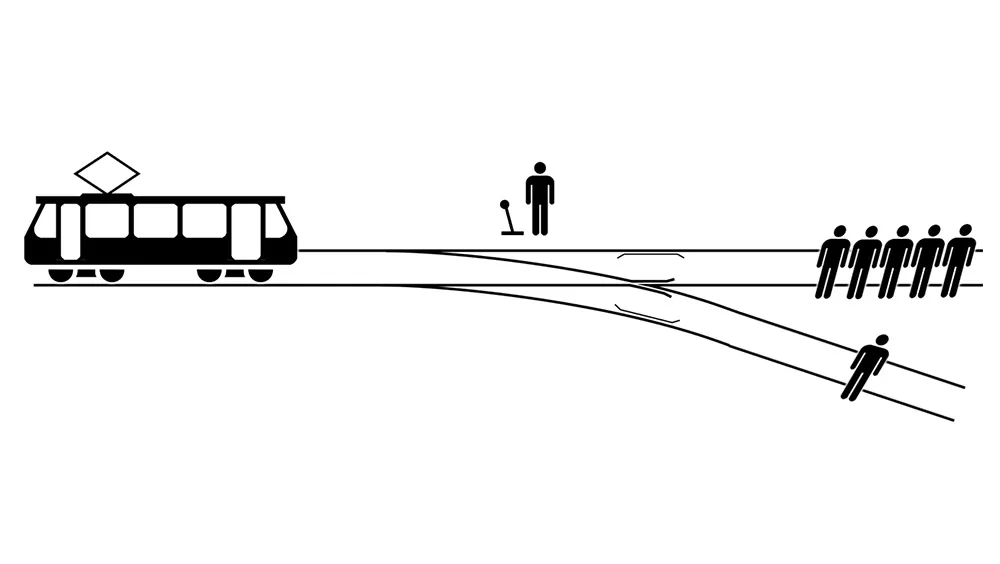

In ethical theory, complicated moral dilemmas are named ‘trolley problems’ after a thought experiment that was introduced by British philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967 (see diagram below).

The experiment asks you to imagine a runaway trolley (tram) travelling at breakneck speed towards a group of five people. You are standing next to a lever that can switch the trolley to a different set of tracks where there is just one person. What’s the right thing to do?

The two main ethical theories disagree about the morally correct course of action in trolley problems. Humans also disagree with which is the best course of action.

Studies show that most people will not pull the lever and therefore fall on the side of the deontological theory. MRI scans show that the areas of the brains associated with emotions light up when these people considered the question. Their thinking goes that to pull the lever knowing about the one person on the side track would be to take an action intended to kill the one.

Deliberately acting to use one person to benefit five others is considered wrong, irrespective of the outcome. Here, standing by and doing nothing is acceptable because as there isn’t an act, there can’t be a ‘wrong’ deliberate intention. The death of the five is only an unintended side effect of doing something perfectly acceptable: nothing.

But a minority feels very strongly that consequentialism is preferable and MRI scans of their brains show more stimulation of logical reasoning areas when considering the problem. They would pull the lever because one death is a much better outcome than five deaths, and whether there was a deliberate intention to kill or not is irrelevant – only the outcome matters.

Similarly, if we think back to our earlier scenario of the passenger travelling on the mountain road, then consequentialist theory would claim that it makes sense for the car to kill them because two children would be saved. And saving two lives is preferable to saving one.

Acting in accordance with either theory is considered to be ethically principled behaviour. In the world of law, judges have to recognise that some actions they don’t agree with are nonetheless still morally acceptable. Respecting others’ ethical reasoning is one way we recognise and treat other humans as moral agents with equal status to ourselves.

This is an important – although subtle – part of our Western ethical consensus today, because we believe that being faithful to our ethical beliefs contributes towards our well-being. This makes the problem more difficult for designers of autonomous driver software: there isn’t a single moral standard expected of human drivers in these dilemmas. Whichever theory they choose, they will end up offending the morals of ethically principled customers who favour the other theory.

Imagine, purely speculatively, that engineers tend to fall in the consequentialist minority and therefore design consequentialist driver software. However, imagine that the majority of customers are deontological. The engineers would have imposed their own moral preferences on many people who do not share the same ideologies.

Being true to one’s moral convictions is an important part of human well-being and our sense of self, so we run the risk of inadvertently breaking a moral principle of our societies and adversely affecting the well-being of other people.

Read more about transport:

- UK’s first hydrogen train to make its debut

- Where should you sit on a bus to avoid travel sickness?

- Five innovative vehicles delivering the future of transportation

I co-authored a paper with Dr Anders Sandberg, an expert in ethics and technology. In the paper, we suggested we could get around the problem of different principles by developing code that would follow either consequentialist or deontological reasoning in a trolley problem scenario.

The passenger could selected their chosen principle at the start of their journey. This would preserve the basis of respect for moral agents that allows our society’s ethical and legal system to deal with the two different ways that people make their decisions about trolley problems.

We can’t have a piece of code that decides between the theories for us. Human moral preferences seem to be a result of learning through praise and blame, not logic.

For now, we have to leave that choice to human users of technology. Until they become moral agents in their own right, autonomous cars will act as what Sandberg has called a “moral proxy” for the users’ own human morals. In other words, we will select how they choose to act.

- This article first appeared in issue 292 ofBBC Science Focus–find out how to subscribe here