Australia is home to some truly iconic mammals, capable of astonishing evolutionary feats. I’ve spent the last 20 years trying to get to know them better, through ecological fieldwork across Australia’s diverse habitats, and a career working with specimens in zoology museums (as well as reading everything I can about them), and I wrote my new book, Platypus Matters: The Extraordinary Story of Australian Mammalswith the aim of celebrating their lives, their roles in recent history, and their place in the world today.

Their natural history can be surprising. Platypuses, for example, are one of a tiny number of mammals that can detect electricity: with their ears, eyes and nostrils closed, they sense the underwater world through the electrical impulses given off by the nerve signals controlling their prey’s muscles – including their heartbeats.

They are also one of the world’s only venomous mammals. The males have large ankle-spurs attached to venom glands, which are used in fights over females during the breeding season, and as such are the only known animals to be seasonally venomous. And being mammals, they produce milk… but they have no nipples.

Among the marsupials, wombats are one-of-a-kind. Their teeth never stop growing, they poo cubes, and they defend themselves with reinforced rears.

And in one species of wallaby, the females are never not simultaneously lactating and pregnant – with a differently aged embryo in each of their two wombs, and two differently aged babies suckling milk, one small one inside the pouch and one large one sticking its head in from the outside. Another kind of wallaby can replace its teeth continuously, like sharks.

Then there are antechinuses – minute carnivorous marsupials whose males don’t see their first birthday, as their frenzied sex lives take so much energy that their immune systems fail. This is all to the benefit of antechinus females, who are then left in a world with no adult males with which to compete for food.

As well as telling their stories, in Platypus Matters I explore how the wider world came to know these creatures, and what that means for their conservation. When they were first introduced to western scientists, the biology of platypuses and their fellow egg-laying mammals, echidnas, became a touchstone for the battle around evolution – they were quite unlike anything anyone in Europe had seen before.

Early colonial reports of Australian mammals are rife with descriptions that paint a poor picture of these incredible species, and those narratives continue to impact the world’s relationship with them today, and with Australia as a whole.

Those accounts were characterised by a stubborn insistence that platypuses, echidnas and marsupials are somehow more primitive than the mammals of Europe and the Americas. This reputation haunts me, and so in my book, I describe the often-misunderstood mammals of Australia in all their glory, and why it matters how we talk about them.

Read more about mammals:

- Mammal evolution: Ancient mammals that lived in the age of dinosaurs

- Do other mammals go through the menopause?

- Prehistoric mammals bulked up to survive in the changing post-dinosaur world

- Do any mammals other than humans have ‘whites of the eyes’?

5 of the best books on mammals

Beasts Before Us

Elsa Panciroli

One of the reasons I am drawn to Australia is that it is the only place – along with neighbouring New Guinea – where all three major groups of mammals can be found together: marsupials, egg-laying mammals, and placentals like us.

The very existence of this diversity today hints that the evolutionary history of the fur-bearing, milk-giving group to which we humans belong is going to be a fascinating story. Elsa Panciroli tells this tale brilliantly – engaging, enthusiastic and expert – writing from the point of view of an accomplished palaeontologist with a gift for writing.

She makes clear that the science of fossils is a very modern one, combining the latest imaging technology with engineering techniques to analyse the incredible specimens at the heart of the subject. And those specimens truly are astonishing.

Beasts Before Us destroys the myth that our ancestors comprise solely of miniature creatures scampering around in the shadow of the dinosaurs: they were large, impressive players in their ecosystems. Panciroli’s account of the last 300 million years weaves in stories from her time on fieldwork, in museums and in the lab, and introduces a whole host of pioneering palaeontological heroes who have shaped our understanding of what it means to be a mammal. This book is full of surprises.

Spying On Whales

Nick Pyenson

Every day, on the way to my office, I pass under the 21-metre skeleton of a fin whale, hanging in the entrance of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge. If you stand there for any length of time, you are guaranteed to hear someone whisper “Wow”. Whales are the very definition of awesome – the largest animals to have ever lived. For anyone who has seen them alive, the encounters are literally transcendental: beyond the range of normal human experience.

Unsurprisingly then, a lot has been written about these giant mammals – much of it successfully evoking the wonder of whales. For me, however, where Spying On Whales stands apart is that it combines their fascinating evolutionary history – told through fossils and modern museum specimens – the extraordinary natural history of living, breathing whales, and current conservation science.

Nick Pyenson lives in all three worlds, and takes us from palaeontological excavations, to studying their wild behaviours, to the world’s biggest autopsies. One of many thoughts that sticks with me from this book is about bowhead whales, which can live for over 200 years. Due to the speed at which ice is melting, a calf born today will grow up to experience an Arctic unlike any bowhead has seen before.

Flames of Extinction

John Pickrell

Australia’s habitats are breathtaking in their scale and diversity, but when undertaking fieldwork across the country, there are few places in which I do not feel some sense of loss for the species that are missing. Australia has the world’s mammal extinction capital. Over a third of the mammals worldwide that have gone extinct since the British invaded Australia were lost from that one country. And many of those that survive have been driven into a tiny fraction of their former ranges.

On the whole, these losses were incremental, but over the fire season of 2019-2020 things got worse very quickly. The world watched in horror as Australia burned in the worst bushfires in recorded history. Flames of Extinction is the first book to tell the story of the ‘Black Summer’, in which three billion vertebrates are thought to have lost their lives or their homes.

Science writer John Pickrell travelled the country, speaking to the army of ecologists, Indigenous rangers and volunteers who risked so much to rescue wildlife and habitats from the flames. Although there is much to be sad for, Pickrell tells the story engagingly and honestly as a witness and as a journalist. By focusing on the work people are doing to protect Australia’s unique wildlife, he finds the hope where he can.

The Missing Lynx

Ross Barnett

The species I grieve for in Australia were lost recently and totally (they lived nowhere else), but closer to home the role-call of mammals is also a lot shorter than it ought to be. Over recent millennia, an incredible range of beasts has disappeared from the British Isles.

In The Missing Lynx we learn about Britain’s lost mammals: woolly mammoths and rhinos, huge cave bears and their slightly smaller relatives, cave lions and cave hyenas, sabretooth cats, massive species of cattle and deer, as well as wolves, beavers and, yes, lynx. Each chapter describes what we know about the species in question (and how we came to know it), when they became extinct, and the potential or actual role of humans in their extinction.

Like the authors of Spying on Whales and Beasts Before Us, with a mix of work on fossils in museums with wild animal encounters palaeontologist, Ross Barnett brings his personal perspective from a place of deep fascination.

There are delightful ‘tales from the bush’ and extremely readable accounts of their own scientific discoveries across their careers. Barnett tells his stories in the voice of a person clearly excited by the things he has been studying all his life, and with a dry sense of humour. His writing style makes you feel like he is talking to you over a pint.

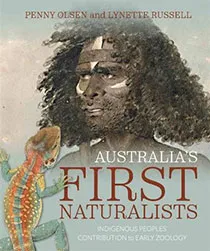

Australia's First Naturalists

Penny Olsen and Lynette Russell

In the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, where I work, labels on many specimens show they were donated by some of the biggest names in the history of science, from Darwin and Wallace to Gould and Audubon. These collections constitute the physical evidence for ground-breaking scientific discoveries.

However, in reality, we are finding that many of the specimens were not actually collected by the famous (typically male, typically white) names scrawled on the labels. They often heavily depended on Indigenous expertise and labour to collect specimens and survive in unfamiliar territory.

On this theme, Australia’s First Naturalists is an exquisitely researched book that makes clear just how much early western zoology of the country was dependent on contributions from Aboriginal Australians. European scientists were thoroughly indebted to Indigenous guides and collectors for much of what they learned about natural history, and for specimen-collecting.

Olsen and Russell have scoured archives of key European explorers and naturalists to tell the story of those First Nations people who had a profound impact on what we now know about Australia’s mammals, allowing us to celebrate them alongside those big names who, to date, have been given most of the credit.

More reading lists:

- 7 of the best cat books to help you understand your feline friend

- 7 of the best smart thinking books to read in 2022

- 7 of the best physics books, according to physicist Suzie Sheehy

- 21 of the best wildlife and nature books for 2022

Platypus Matters: The Extraordinary Story of Australian Mammals by Jack Ashby is out now (£20, William Collins).