August 1933. It was a warm summer’s day when Mr and Mrs Spicer were driving along the road adjacent to Loch Ness.

Suddenly, lurching from left to right across the road, appeared an amorphous, monstrous apparition that moved with a peculiar bounding motion. An object that looked like the head of a small deer was located somewhere about its middle.

The Spicers’ sighting was one of the very first to describe the Loch Ness Monster, a creature known more popularly today as ‘Nessie’.

It’s a classic sighting, regarded as part of a field – cryptozoology, the hunt for unknown and typically monstrous animals – seen by its proponents as challenging mainstream science.

Read more about the search for the Loch Ness Monster:

- Loch Ness Monster DNA reveals 'plausible' explanation for sightings

- Loch Ness: How eDNA helps us discover what lurks beneath

- Operation Deepscan: the hunt for the Loch Ness Monster

- Loch Ness Monster: A timeline of sightings and searching

The Spicers’ account is one of many Nessie sightings, and only one of thousands of monster sightings worldwide. Other famous monsters include Bigfoot (also known as Sasquatch), the Yeti, the dinosaur-like Mokele-Mbembe of the Congo, and the terrifying winged Ropen of New Guinea.

But in a way, the Spicer sighting epitomises cryptozoology as a whole. The more we’ve learnt and the more data we’ve gathered and analysed, the more it seems that all these accounts have logical explanations.

Founding the International Society of Cryptozoology

The Spicer sighting coincided with a specific cultural event, namely the release of the now-classic movie King Kong. Don’t forget, this film features dinosaurs and other animals in addition to its eponymous anti-hero.

Everyone was talking about King Kong in the summer of 1933, and we know that the Spicers had seen the movie. They’d been culturally primed: dinosaur-like monsters were metaphorically lurking in their minds.

Furthermore, the Spicer sighting can be explained if we just look at enough of the details. The bounding motion, that small ‘deer’s head’, and the location of the encounter (it occurred next to a track in the woods where a vegetated verge meets the road) all indicate that their ‘monster’ was simply a group of deer bounding in front of them, a fawn in its midst.

This is exactly what Rupert Gould, the investigator who brought the Spicer sighting to attention, concluded, later regretting his inclusion of the account in his 1934 book, The Loch Ness Monster And Others.

Additional Nessie sightings rolled in during the 1930s, laying the foundations for a school of thought in which the monster’s existence came to be taken semi-seriously. This phase persisted into the 1960s and 70s.

During these decades, rare snippets of film and blurry photographs were put forward as support for the creature’s existence. In 1972, underwater photos of Loch Ness appeared to show the flipper of a gigantic, plesiosaur-like creature.

Surely, believers said, confirmation of Nessie’s existence was but weeks away.

This might sound like an optimistic view today, but it shows the extent to which cryptozoology had captured the public’s imagination.

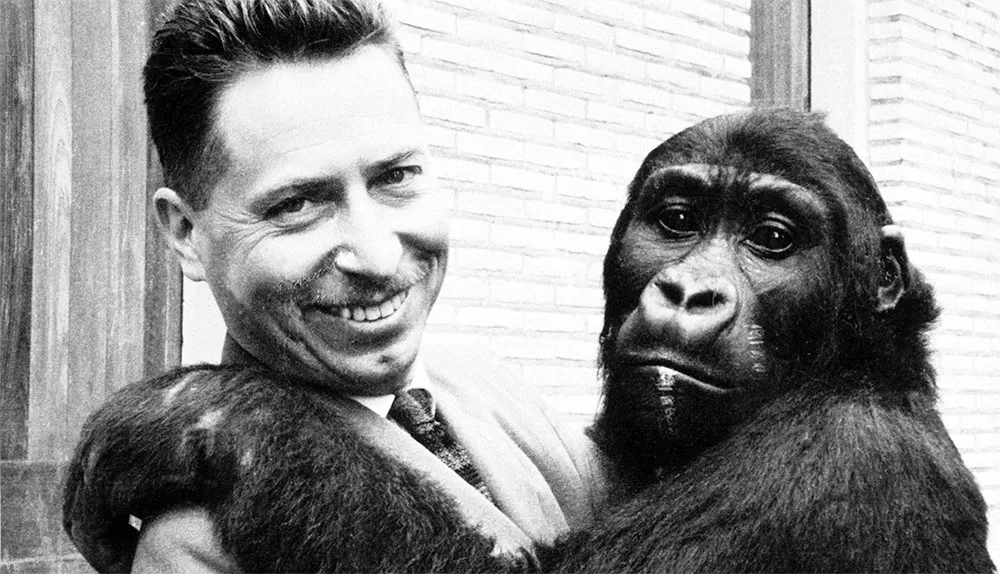

The man responsible for much of this excitement was Bernard Heuvelmans. In the mid-1950s, this Belgian-French zoologist published a successful book titled On The Track Of Unknown Animals, in which he put forward the case for the existence of mystery beasts neither accepted nor taken seriously by science.

He pointed to the 19th- and 20th-Century discoveries of a range of large animals – including the okapi, Komodo dragon and mountain gorilla – as support for his view that other large creatures were still out there to find. Heuvelmans’ writings developed a substantial following.

The daring proposal that giant mystery primates, lake and sea monsters, and surviving dinosaurs and pterosaurs might really exist – an idea that had always been present at the fringes of the zoological world but was dismissed due to lack of evidence – achieved a modicum of respectability when its proponents elected to form an International Society of Cryptozoology (or ISC) in 1982.

Over the years, scant fragments of data were put forward as support for the existence of the mystery creatures that Heuvelmans and the ISC endorsed.

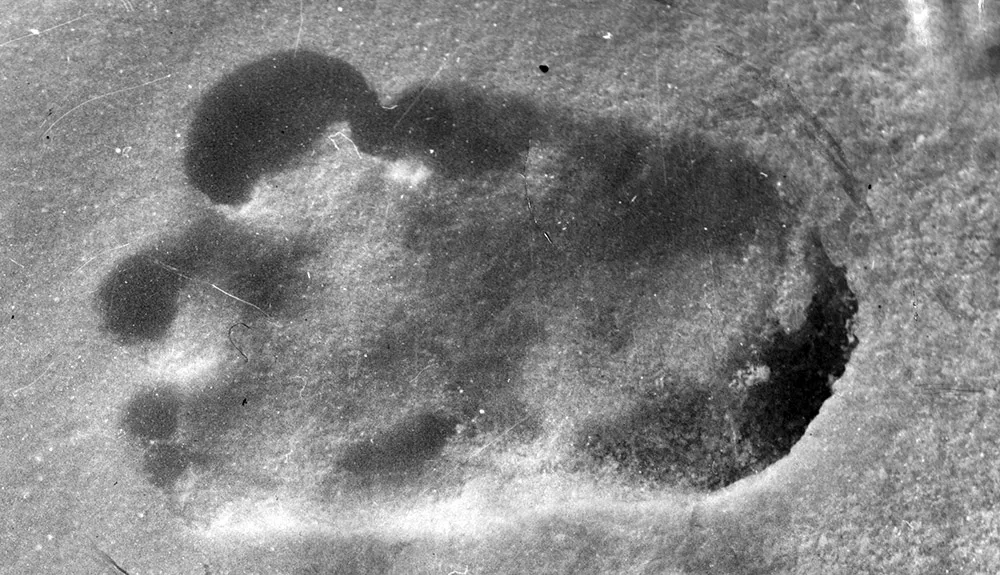

Key among these were the alleged Nessie photos of the 1930s, 1960s and 1970s; a supposed Yeti footprint photographed in the Himalayas in 1951; the notorious film shot in California in 1967 said to depict a female Bigfoot walking alongside a creek; and tracks and other evidence also purported to belong to Bigfoot.

Nessie and other bogus beasts

Heuvelmans and his followers claimed that mainstream science displayed a disinterested, blinkered approach to these pieces of evidence, and to the study of mystery animals in general.

In reality, qualified scientists investigated this evidence to a considerable degree, concluding that all of it could either be completely explained or labelled as significantly problematic.

The photos that claimed to show Nessie all turned out to be hoaxes, or misinterpretations of waterbirds, waves, boat wakes or underwater objects like chunks of wood. Investigations published since 1999 show that the most famous Nessie photos variously depict a toy submarine, a blurry swan, a wave and an upturned kayak.

The alleged Yeti footprint of 1951 has irregular depressions at the left and right edges and heel, showing that it isn’t a real primate track but a hoax manufactured by human hands.

As for the 1967 Bigfoot film, an enormous amount of circumstantial evidence shows how Roger Patterson, the cameraman, planned for years to set up a hoaxed scene exactly like the one he filmed.

If photographic evidence has failed to pass the tests, what else might support the existence of monsters? An idea popular among cryptozoologists is that Nessie, Bigfoot and other mysterious beasts escape detection because they inhabit regions of the world that are remote and little explored.

But is this true? Loch Ness is no remote Highland refuge, but has long been an important place for military campaigns, transportation and settlement.

It’s regularly traversed by ships, and became connected with other waterways in the 19th Century, ultimately forming the 97km-long Caledonian Canal.

Loch Ness also fails as the sort of place where giant, unknown animals could survive. It’s home to birds, fish of several species and small crustaceans. Otters frequent its surface, seals visit on occasion, and deer sometimes swim across it.

But this is a scarce, low-diversity collection of creatures for a lake of this size and latitude. Indeed, the organic productivity of Loch Ness is so low that even the most optimistic calculations show that a population of large aquatic animals could not survive here, and certainly not for generations.

Key terms

Bigfoot

A giant, hairy, man-shaped monster famous for leaving human-like footprints. Originally associated with California, cryptozoologists believe that it occurs across North America and even beyond.

Cryptid

An animal – argued by cryptozoologists to represent an unknown species or subspecies – that has been described by witnesses but remains unconfirmed by science.

Crypto-zoology

The investigative field that aims to discover and study animals that are alleged to exist, but are as yet only known from anecdotal evidence.

Mokele-Mbembe

An elephant-sized water monster of the Congo region, imagined by proponents to be a long-necked herbivore and perhaps a surviving sauropod dinosaur.

Ropen

A giant, winged beast of New Guinea, said to be bioluminescent and to eat human corpses. Its proponents – most of whom are creationists – believe it to be a surviving pterosaur, a flying reptile otherwise thought to have died out 66 million years ago.

Similar arguments can be applied to other monsters. It’s true that Bigfoot is associated with the wilds of British Columbia and Alaska, but what are we to make of the hundreds of reports from New York, Florida, and every other state across the US mainland?

It would appear to be the commonest, most widely distributed non-human primate on the planet, occurring in places that cannot reasonably be regarded as potential haunts for a huge, as-yet-undiscovered mammal.

Furthermore, it apparently lives right under the noses of hundreds of qualified biologists, conservationists and ecologists – any one of whom, make no mistake, would be rocketed to stardom (and, more importantly, tenureship) if they proved the beast’s existence.

Unlike Nessie, Bigfoot at least has some hard evidence put forward in support of it. But none of this has withstood scrutiny, and a long history of hoaxing and misinterpretation means that there’s nothing convincing surrounding Bigfoot’s existence. Even excellent ‘gold standard’ tracks have been shown to be faked.

During the 1990s, anthropologist Grover Krantz argued that several plaster casts taken of Bigfoot tracks displayed marks made by the tiny ripples and grooves on primate feet, known as ‘dermal ridges’.

Similar marks were noticed on other tracks, and they were taken by proponents as powerful support for the reality of Bigfoot.

However, in 2006, investigator Matt Crowley showed via a series of experiments that the marks were actually ‘desiccation ridges’. These are formed in plaster as it sets: they are not proof of the biological reality of Bigfoot, but an accidental consequence of plaster casting.

More recently, the claimed discovery of Bigfoot DNA has been used to support the ape’s reality. A 2013 study claimed to have catalogued both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from Bigfoot, showing that the beast is a hybrid between Homo sapiens and a second species of unknown ancestry.

But independent checks by several geneticists revealed the results to be bogus, with the DNA found to be a mix belonging to various North American mammals.

Why do people still report sightings?

Decades of investigation have shown that a significant percentage of classic monster sightings can be explained as hoaxes or confused encounters with known animals or phenomena.

What’s more, virtually all photographic ‘evidence’ can be explained or dismissed, and ecological problems are attached to the supposed existence of various monsters. For all this naysaying, however, the fact remains that people continue to report sightings of these beasts. Why?

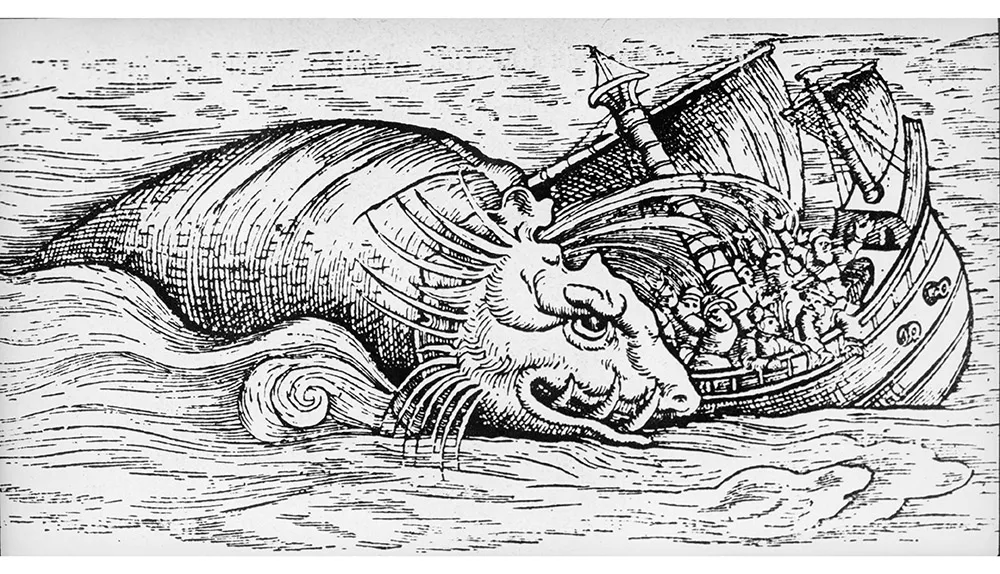

For years, folklorists and anthropologists have argued that modern ideas about monsters represent the vestiges of age-old folk beliefs in which dangerous places – deep lakes, dark forests, treacherous mountains – are associated with frightening creatures.

The ‘biology’ and ‘behaviour’ of these animals is then reinforced by tales, anecdotes and artwork, passed down the generations.

This explanation has increased in popularity since 1988, when folklorist Michel Meurger showed how people’s ideas about lake monsters in northern Europe were linked to the folklore of their culture.

In other words, our cultures have primed us to imagine monsters whenever we see such things as dark shapes beneath the water, or shadows in a forest. The psychological term for this is ‘perceptual expectancy’.

Psychology provides support for the idea that monsters are almost hardwired into our consciousness.

Controlled experiments published since 2010 have shown how people ‘see’ monstrous apparitions, perceive frightening distortions of known objects, and have a distorted sense of size perception when they’re afraid or confused, or while making observations in dim conditions.

Read more about the Loch Ness Monster and other beasts:

- 'Flying Spaghetti Monster' caught on camera

- 'River Monster' first known dinosaur to have lived in water

- Neil Gemmell: The genetic hunt for the Loch Ness Monster

So are we left with any compelling reason to think that massive, mysterious animals like Nessie and Bigfoot really exist?

No, and despite extensive work and decades of searching, both monster proponents and sceptics have failed to produce any positive evidence that’s even vaguely compelling. If there’s any answer to the vexing question of why people claim to see the monsters, it’s that we are all the products of those cultures to which we belong.

We are complex, deluded creatures, typically refusing to abandon the fact that we’re frequently tricked by our senses, our memories, and even our abilities to make sense of what we see.

- This article first appeared in issue 298 of BBC Science Focus–find out how to subscribe here