People of all ages who have had two doses of the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine produce high numbers of antibodies, new research suggests.However, there is not enough data to say how protected someone may be from the virus based on a positive antibody test result, and it does not mean they are immune.

For the first time, the research, known as REACT-2, studied participants in England who have received a COVID-19 jab, and also gathers insight into how different groups feel about vaccines.

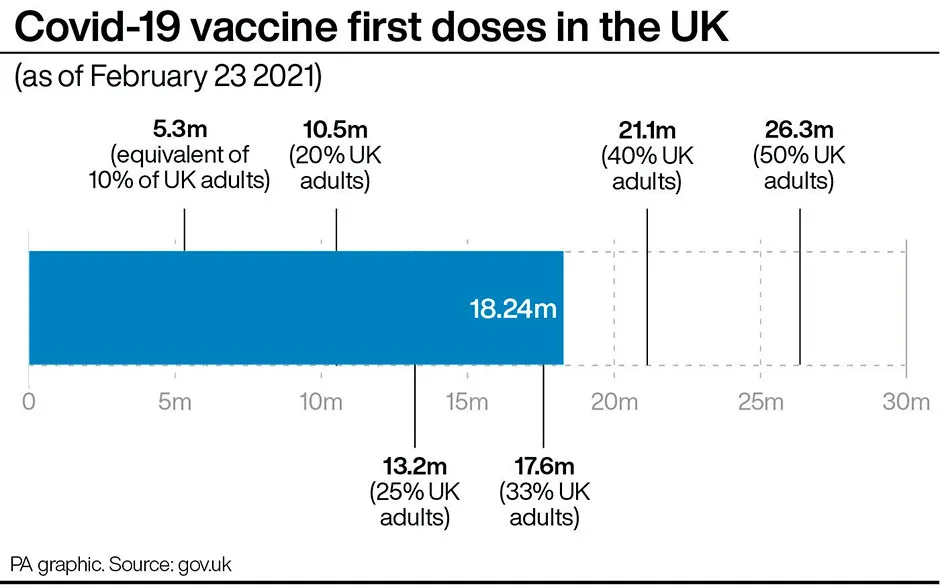

More than 154,000 participants tested themselves at home using a finger prick test between 26 January and 8 February, showing 13.9 per cent of the population had antibodies either from infection or vaccination. More than 17,000 of these participants had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose.

The data indicates that 87.9 per cent of people over the age of 80 tested positive for antibodies after two doses of the Pfizer vaccine.This rose to 95.5 per cent for those under the age of 60 and 100 per cent in those aged under 30.

The Imperial College London and Ipsos MORI study, which has not been peer-reviewed, also shows high confidence levels in the vaccine. More than 90 per cent of those surveyed reported that they would be willing to accept, or had already had a vaccination. But vaccine confidence varied by age, sex and also by ethnicity, highest in those of white (92.6 per cent) and lowest of black (72.5 per cent) ethnicity.

Read more about the Pfizer vaccine:

- Pfizer vaccine: Single dose ‘90 per cent effective after 21 days'

- Pfizer vaccine appears to be effective against UK coronavirus variant

The three most commonly selected reasons for vaccine hesitancy were wanting to wait and see how the vaccine works, concern about long-term health effects, and worries about side effects.Other common concerns shown in free text comments were around current and planned pregnancy, future fertility and specific allergies.

“Overall there’s very high effectiveness in terms of antibody positivity from two doses of the BioNTech, and also from a single dose in people who have had prior infection, that much we know," said Professor Paul Elliott, director of the REACT programme, Imperial College London.

“And also, although there is some fall off in positivity with age, at all ages we get that very good response to two doses of the vaccine. And in terms of the confidence in the vaccine, it’s very, very high, although there are some groups where it’s a bit low, and that includes some ethnic minority groups and some younger people.”

Antibody prevalence in unvaccinated people remains highest in London (16.9 per cent), and in people of black (22.1 per cent) and Asian (20 per cent) ethnicities, and those aged 18-24 years (14.5 per cent).

For individuals who received a single dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech jab after 21 days, the proportion testing positive for antibodies was 94.7 per cent in those under 30, ranging from 73.7 per cent at 60 to 64 years to 34.7 per cent in those aged 80 and over.

In those who had previously had confirmed or suspected COVID-19, 88.8 per cent were testing positive for antibodies, according to the pre-print study.

The researchers say the findings on antibody response following a single dose align with existing research that suggests those aged over 80 take longer to develop a response to infection and the immune response is not as strong.

Antibodies are just one component of the body’s immune response produced by COVID-19 infection or vaccination. Vaccines also induce T-cell related protection, independent of antibody production.Scientists say T-cell responses may vary significantly between vaccines and may be particularly important in influencing duration of protection.

The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) noted that in Pfizer’s clinical trial, protection against coronavirus was very high (89 per cent) between 14 and 21 days after vaccination, despite very low levels of antibodies measured at the same time.This suggests that early antibody response does not correlate with clinical protection, researchers say.

“Our findings suggest that it is very important for people to take up the second dose when it is offered," said Professor Helen Ward, lead author for the REACT study of population prevalence.

“We know that some groups have concerns about the vaccine, including some people at increased risk from COVID-19, so it is really important that they have opportunities to discuss these and find out more.”

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against the Ebola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: