A newly discovered 410-million-year-old fossil of an ancient armoured fish could turn the evolution of sharks on its head.

Today, the majority of vertebrates have skeletons made of bone. But sharks and their relatives, such as rays and skates, have lighter, more flexible skeletons made of cartilage. Conventional wisdom has stated that cartilaginous fish evolved first, with bony fish (like tuna and mackerel) evolving later. Sharks, however, retained their cartilaginous skeleton.

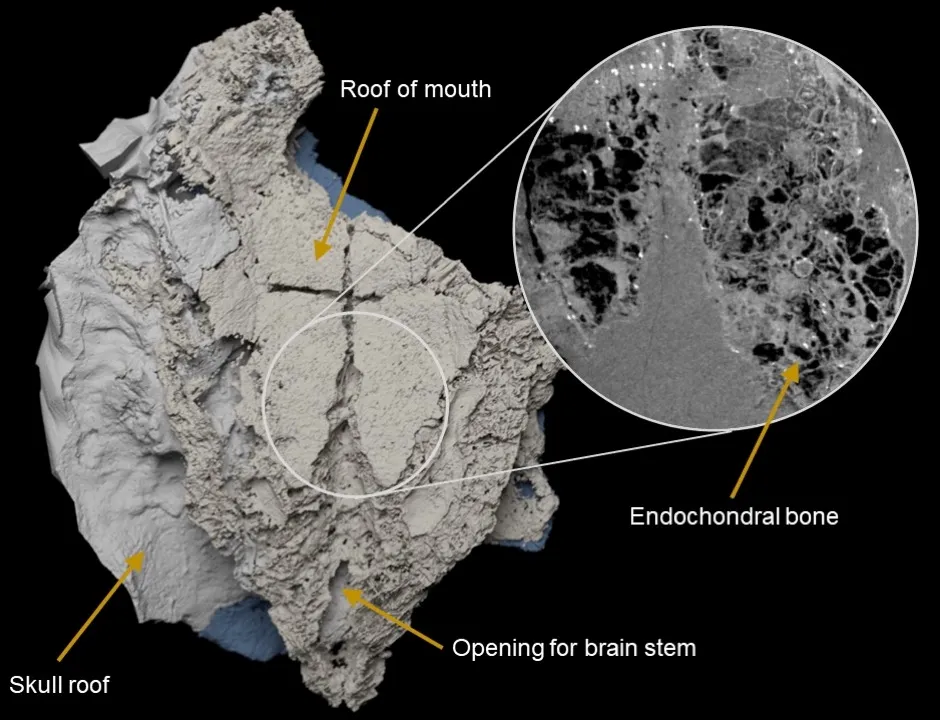

The new fossil, which was discovered by an international team of researchers, has been named Minjinia turgenensis. It belongs to a group of armoured fish called the placoderms, and is closely related to the last common ancestor of both sharks and bony fish. When the team uncovered part of its skull, including its braincase, they found that it was made of bone. This suggests that sharks may have first evolved bone and then lost it again, rather than keeping their initial cartilage state throughout their 400 million years of evolution.

“If sharks had bony skeletons and lost it, it could be an evolutionary adaptation,” said Dr Martin Brazeau, who took part in the research. “Sharks don’t have swim bladders, which evolved later in bony fish, but a lighter skeleton would have helped them be more mobile in the water and swim at different depths. This may be what helped sharks to be one of the first global fish species, spreading out into oceans around the world 400 million years ago.”

Read more about sharks:

- Cold War radiation helps scientists to calculate whale sharks ages

- Prehistoric megalodon was a mega-shark that had fins as large as an entire adult human

- First ever omnivorous sharks identified

The majority of early fish fossils have been uncovered in America, Australia and Europe, but new fossils have recently been found in China and South America. M. turgenensis was discovered in Mongolia, in rock formations that have never been searched before. The team will now be sorting through the other material they have found, which may help them piece together shark evolution even further.

Reader Q&A: Why have hammerhead sharks evolved their distinctive heads?

Asked By: Anonymous

These sorts of ‘why’ questions are tricky. We can get ideas from how the various hammerhead species use their bizarre ‘cephalofoil’, but those aren’t necessarily why it originally evolved. Nor why other sharks manage fine without it. Basically, the head provides extra lift and manoeuvrability, wider eye separation and greater area for sense organs such as smell and electric-field detection. In some species, it’s used to pin down struggling prey.

However, unless something’s evolved separately several times over, it can be difficult to state with confidence what selection pressures were involved. Fortunately, hammerhead species with very different head shapes and sizes exist. Very recent DNA-based family trees of these eight species reveal something unexpected: species with astonishingly wide heads, like the winghead shark (Eusphyra blochii), branched off first. That implies the cephalofoil started huge before evolving into the much smaller heads seen in, say, bonnethead sharks (Sphyrna tiburo). It’s been suggested that this indicates a role for extreme sensory advantage – increased binocular vision or olfaction – rather than hydrodynamics.

Read more: