Past beliefs can often seem funny and bizarre, and none more so than the view held for much of the 19th Century by everyone from the average member of the public to major cultural figures and leading scientists. They were all convinced that it was possible to determine an individual’s personality by feeling the bumps on their head.

Known as phrenology (the word means ‘study of the mind’), this guff was believed by everyone from Karl Marx to Queen Victoria, and it featured in novels such as Jane Eyre as well as in the Sherlock Holmes stories – Moriarty makes a disdainful phrenological remark about Holmes when the pair first meet.

Popular books on phrenology sold hundreds of thousands of copies. All this, despite being complete nonsense.

Franz Joseph Gall, the inventor of phrenology

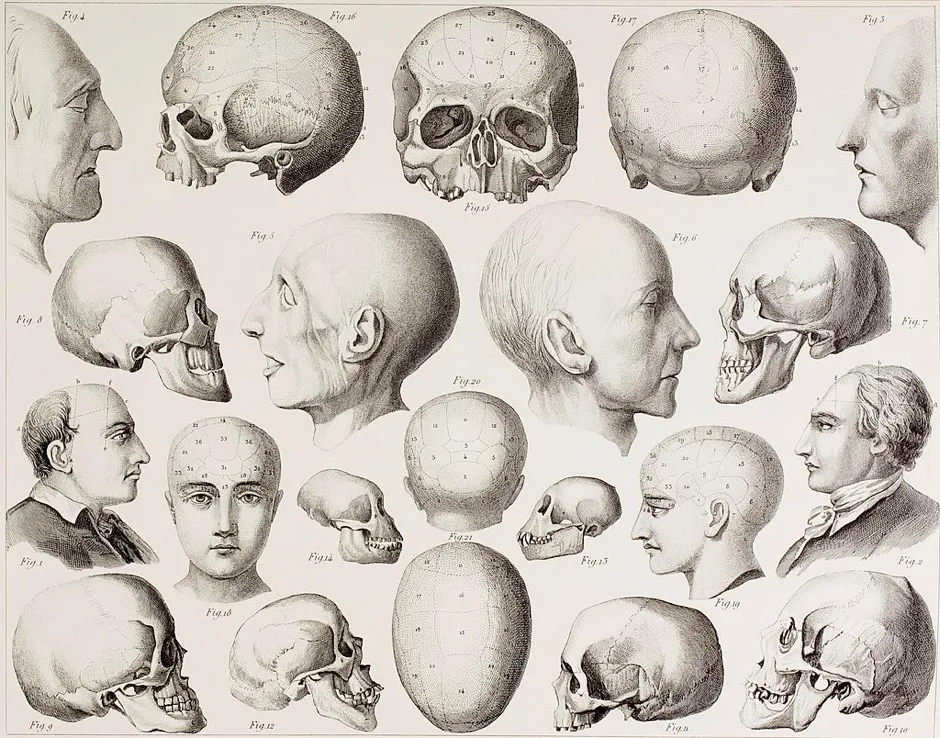

Initially known as cranioscopy, phrenology was the brainchild of Franz Joseph Gall, a Viennese physician.

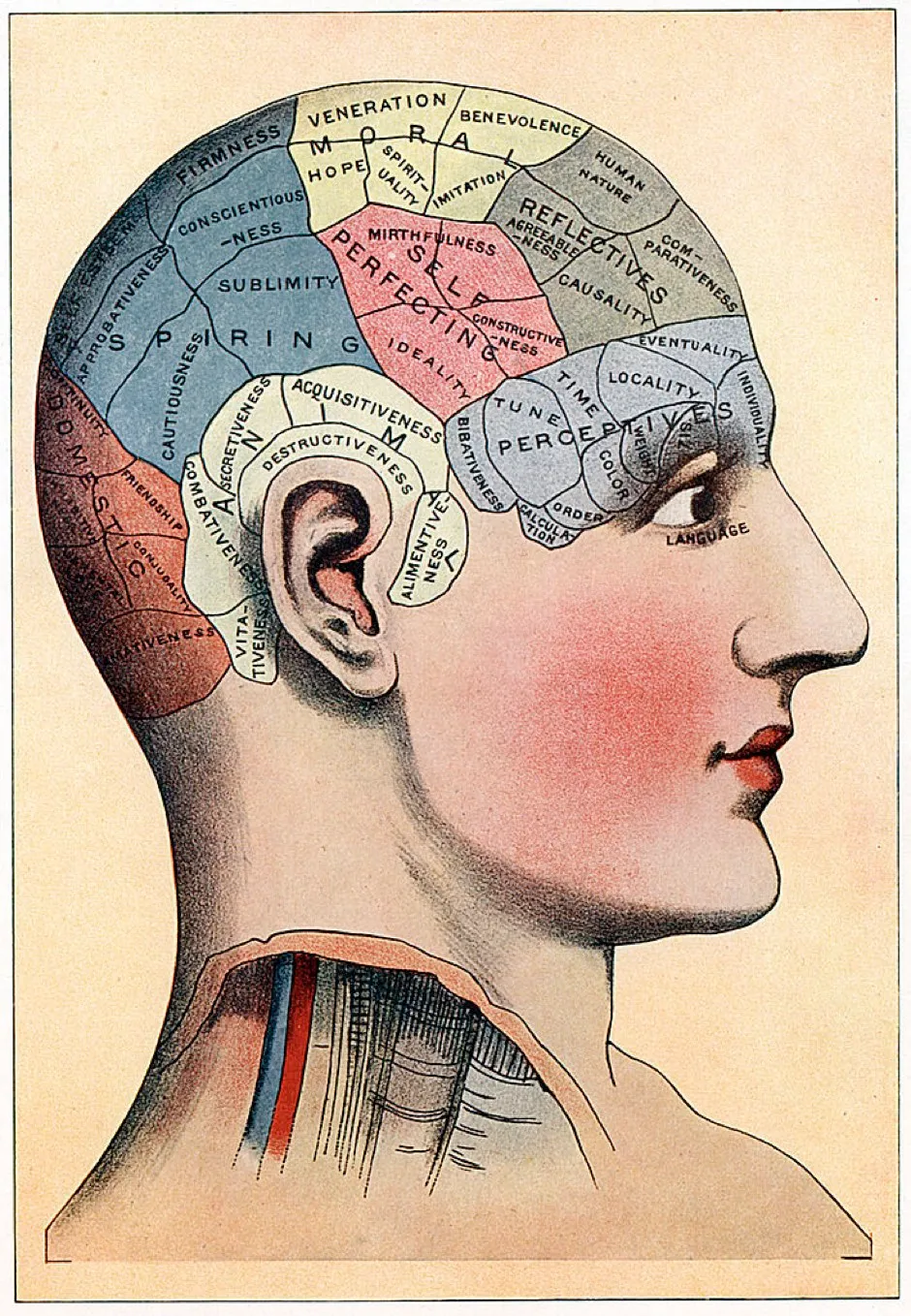

During the 1790s Gall suggested that a person’s character could be divided up into a number of mental faculties, each of which were produced by a particular organ in the brain.

Above all, Gall claimed that it was possible to detect the relative size of these organs by feeling the shape of the skull (he never addressed the fairly obvious problem that the bony skull is thicker in some areas than others, and that it is covered in muscles and skin that make it difficult to measure its shape precisely).

Despite being completely spurious, Gall’s theory was based on three insights that still form the basis of our understanding of the link between brain, mind and behaviour.

Firstly, Franz Gall considered that ‘the brain is the organ of all the sensations and of all voluntary movements’.

Second, Gall assumed that there was a localisation of function, in that very precise parts of the brain were responsible for different aspects of thought and behaviour.

Finally, Gall explained how humans shared most of their psychological faculties, and the underlying organs, with animals. Only eight of his 27 faculties were unique to humans – wisdom, poetry and suchlike.

Gall claimed that this comparative approach enabled him to discover ‘the laws of the organism’, even though the link between behaviours in animals and in humans was sometimes tenuous – for example, the faculty of pride was taken to be identical to the propensity of mountain goats, birds and so on to live in high places (the word Gall used for ‘pride’ was ‘hauteur’, which also means ‘height’).

Read more about Victorian medicine:

- Joseph Lister and the grim reality of Victorian surgery

- Five quick facts about Victorian quacks

- The Smile Stealers: 10 pictures from the history of dentistry to make you squirm

In 1815, Gall fell out with his phrenological colleague Johann Spurzheim. At one level, the differences seemed trivial – Spurzheim described eight extra organs and faculties and also introduced a different set of psychological terms. But the dispute ran much deeper.

Franz Gall had argued that the faculties were innate and fixed, and that, if expressed in excess, could give rise to less desirable behaviours such as lustfulness, fighting, or deceit.

For Spurzheim, immoral or criminal behaviours were the consequence of experience; education could alter the size of the brain organs, and therefore change behaviour.

The growing popularity of phrenology

Spurzheim’s more positive, even therapeutic, phrenology was the version that began to capture the popular imagination in Europe and the USA.

Phrenological societies popped up in many countries. In the UK the first members of these societies were professional men and intellectuals, but these groups soon interacted with the Mechanics Institutes and the Literature and Philosophical Societies that were a feature of the growing industrial cities, giving phrenology a real mass following.

Despite – or perhaps because of – this popular interest, intellectuals and physicians were never completely at ease with phrenology. In the pages of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the physician Peter Mark Roget (later author of the eponymous Thesaurus) scoffed at what he called the ‘metaphysical labyrinth of the thirty-three special faculties into which they have analyzed the human soul’.

He went on to dismiss the phrenologists’ suggestion that damage to the brain led to alterations to mental faculties, before concluding that ‘nothing like direct proof has been given that the presence of any particular part of the brain is essentially necessary to the carrying on of the operations of the mind’.

In private, scientists could be even more forthright: in 1845 the Cambridge professor of geology, the Reverend Adam Sedgwick, wrote a letter to his colleague Charles Lyell, describing phrenology as ‘that sinkhole of human folly and prating coxcombry’.

From the late 1840s onwards, phrenology began to wane as a social force. The London Phrenological Society fell apart in 1846, while in France, the timid individually focused changes advocated by many phrenologists seemed completely inadequate as the wave of revolutions that swept through the continent in 1848 crashed over the country.

The path to neuroscience

But that was not the end of phrenology. Not only did it linger on as a somewhat frivolous popular belief (a bit like astrology or crystal nonsense today), above all, cutting edge brain science revealed that one of the key postulates of phrenology – particular functions are localised to particular parts of the brain – seemed to be true.

The first insight came in France, where the scientific community was united in its opposition to phrenology, arguing that all brain activity was the consequence of the whole organ, which acted in a unified and indivisible way.

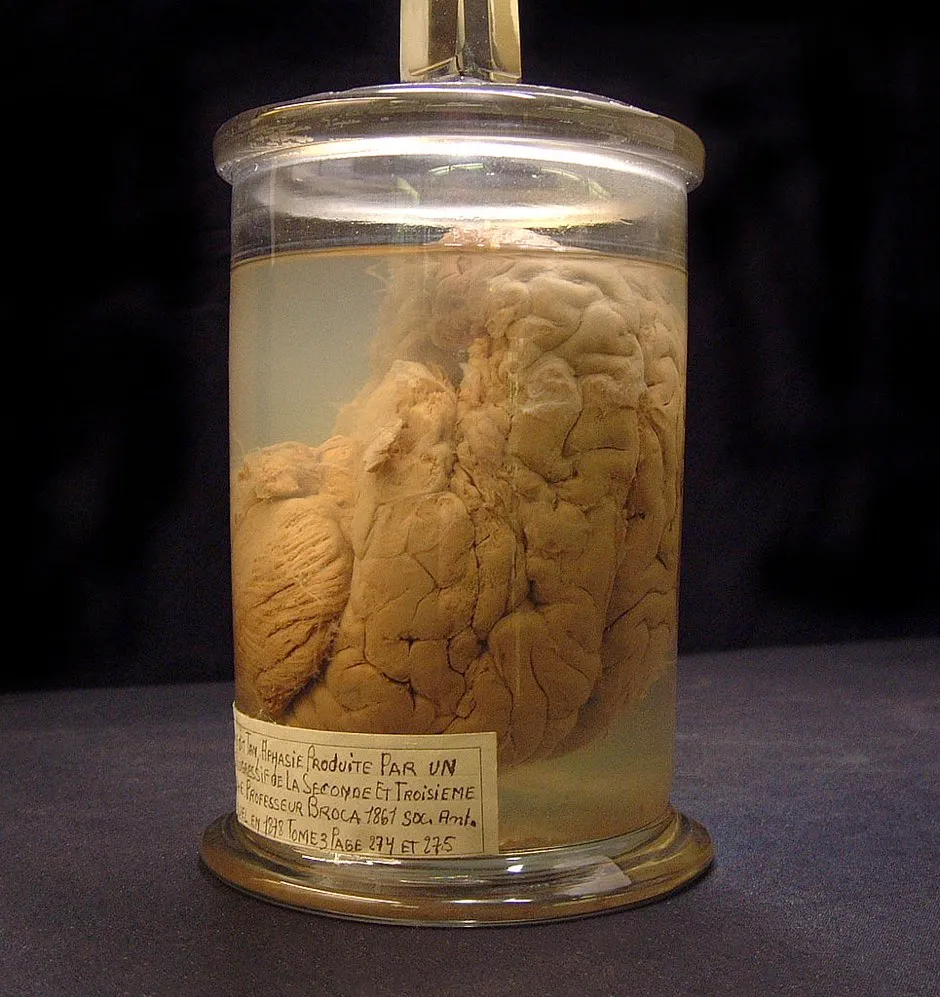

This view – which flowed from Descartes’ philosophy rather than any scientific evidence – was severely shaken in the early 1860s, when leading French surgeon Paul Broca investigated the brains of a series of stroke patients who had difficulty speaking.

To his great surprise, Broca discovered that they all had lesions in the same frontal region of the brain, on the left side. Using strikingly phrenological terms, Broca announced that he had discovered ‘the organ of the faculty of speech’.

Now known as Broca’s area, this region of the brain does indeed control speech production.

A few years after Broca’s discovery, in 1870, two young German researchers, Gustav Fritsch and Eduard Hitzig, reported that dramatic effects could be obtained by gentle electrical stimulation of the outer layers of the brain of an anesthetised dog.

They worked on the cortex, a brain region that everybody accepted did not respond to stimulation of any kind. Surprisingly, Fritsch and Hitzig found that electrical stimulation of one part of the cortex moved the forelegs, of another made the face twitch, and of yet another moved the leg muscles.

In London, David Ferrier, a 27-year-old neurologist, applied this technique to produce a very precise map of the monkey cortex, showing how various motor and even sensory abilities, such as hearing, were specifically localised to small areas of the brain.

These were not psychological ‘faculties’ as the phrenologists had assumed, but were much more basic functions, out of which, in some mysterious way, more complex behaviours and even thoughts might somehow be assembled.

Two studies convinced Ferrier that humans, too, showed localisation of function in the brain.

In 1874, a scandalous but now-forgotten experiment was carried out in a Cincinatti hospital by Professor Roberts Bartholow. Bartholow’s patient, 30-year-old Mary Rafferty, had a nasty scalp ulcer that bared her brain.

Bartholow introduced electrodes into Mary’s brain, noting her involuntary movements and behavioural responses when he turned on the current, much as Fritsch and Hitzig had found with their dog.

Although Bartholow reported that ‘her countenance exhibited great distress, and she began to cry’, he continued the stimulation until she had a fit. He then repeated the procedure two days later.

A short while afterwards, Mary died. Bartholow was heavily criticised for his unethical behaviour and he was forced to make a semi-apology.

Read more about extreme experiments in science history:

- Forbidden medicine: what do we do when medical breakthroughs are unethical?

- Five experiments that might have influenced Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

- Dragon breath, vomiting slugs and pigeon remedies: 8 bizarre medical stories from history

Ferrier was scandalised by Bartholow’s study, but realised that it implied that humans were no different from other animals in terms of their brain organisation.

He became further convinced of this when he noted the similarities between changes in the behaviour of one of his monkeys after it had the front part of its brain removed, and a previously overlooked remark in an 1868 report of an industrial accident that had occurred in 1848 to one Phineas Gage, an American railway labourer.

Gage was severely injured when an iron rod went through the front part of his skull, but he miraculously recovered from his terrible injuries and even travelled widely before dying 12 years later. During his lifetime, Gage was well known because he had survived.

Ferrier noticed that, according to the 1868 paper, Gage had become ‘fitful’ and ‘irreverent’ after the accident. Putting this anecdotal and unverifiable claim together with his observations of his monkey, Ferrier concluded that ‘the phrenologists have, I think, good grounds for localising the reflective faculties in the frontal regions of the brain’.

Nowadays, neuroscience students read about Gage, but they do not learn how the effects of his injuries were re-interpreted, nor do they know the link with the pseudo-science of phrenology.

Phrenology was bunkum, but it helped to lay the basis for understanding brain function in terms of the activity of particular regions, something that continues to be the focus of a great deal of scientific research.

The extent to which there truly is localisation of function, and our brains have a genuinely modular structure, with different processes occurring in different areas, is a matter of debate. To some extent, we are still repeating the arguments phrenology asked of us, ofover 150 years ago.

The Idea of the Brain by Matthew Cobb is available now (£30, Profile Books)