Species-wise, you probably identify as human. But based on the number of cells in and on your body, you are actually more microbe, because trillions of them call you home. Your human genes are outnumbered by microbial genes and, as the scientists exploring our microbial ecosystems (known as our microbiome) are discovering, the armies of tiny freeloaders our bodies host are quietly controlling us. Together, they can govern mood, appetite and immune responses, as well as helping to digest and metabolise foods.

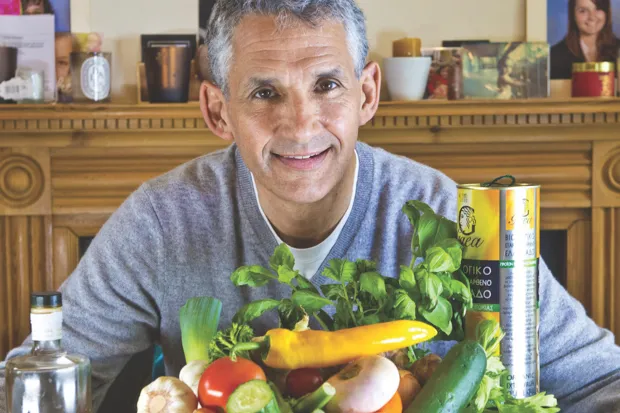

In some ways, our microbes are more influential in shaping who we are and how we feel than our genes, says Prof Tim Spector, who runs a microbiome research unit at King’s College London called the British Gut Project. “I can tell more about someone’s health by getting a detailed screen of their microbes than by screening their genes,” he says, pointing out that we’re 99.7 per cent genetically similar, whereas “we only share about 20 or 30 per cent of our microbes.”

A census of your guts

Spector started The British Gut Project in 2014 to map as many people’s microbiomes as possible, so as to reveal associations between our biomes and health. He had recently started studying stool samples from the vast King’s College twins research registry he’s led for 25 years, and was inspired by microbiologists in the US who had launched a crowd-funded study called American Gut. The shared aim of the British and American Gut projects is to build vast banks of gut data by inviting the public to participate. For a small fee, which is used to fund the work, participants get to discover which rare species they’re harbouring, how their microbiome compares with others in their country and, says Spector, they’re working on adding a “diversity score”, because the more different types of microbes we host, the healthier we tend to be.

The samples collected by the British Gut Project are sent to the American Gut laboratory in San Diego for analysis. British Gut is, essentially, the European wing of American Gut, which is working with an expanding network of researchers around the world, seeking to do the same. All the resulting data are open source and will form part of the ambitious Earth Microbiome Project, a collaborative international push to characterise microbial life on Earth.

There are microorganisms such as bacteria and yeasts living all over our bodies, from toes to nose, which is why the British Gut Project will also accept swabs taken from skin, mouths and vaginas. But the control centre lies in the gut, which some researchers somewhat creepily refer to as the second brain. (Finally, there’s a scientific basis for the idea of ‘gut instinct’.) By analysing the living contents of our guts via stool samples, researchers can identify geographical differences – such as American microbiomes tend to be less diverse than their British counterparts – and links between certain microbes and common diseases.

Currently, says Spector, microbiome knowledge is 10 years behind human genetic research. We’ve only scratched the surface in identifying all the microbes, learning what they do and how they work together. But we have identified a group of microbes that seem to be beneficial in most people. People with diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, food allergies, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), colitis and high blood pressure, says Spector, “tend to lack these beneficial microbes that in other people are protective.”

There are strong links, also, between mental health and gut health. Prof Felice Jacka, who runs the Food and Mood Lab at Deakin University in Australia, first established the field of nutritional psychiatry a decade ago and her research is increasingly turning to microbes. “All the factors that underpin depression from a biological point of view are under the regulation of the gut microbiome: inflammation, brain plasticity, immune activation in the brain, gene expression. It also affects the level of neurotransmitters in the brain and has a very important role in modulating the stress response system,” she says.

Even the effects of foods and drugs on our systems (from antidepressants to cancer chemotherapy) are related to the microbes we have. “If you’re on cancer chemotherapy,” says Spector, “and you have the right type of microbes, you’ll be three times as likely to survive. So everybody going onto cancer chemotherapy should be getting their microbiome tested.” If it’s found that you don’t have the necessary microbes, taking probiotic supplements containing helpful bacteria and making dietary changes, he says, may well improve your chance of living. “American cancer centres are now routinely screening their patients and offering advice,” notes Spector, whereas the gut-chemo axis hasn’t reached British doctors’ agendas yet.

This is one among many examples where taking probiotic supplements has been shown to be effective. “It’s looking like they do work for a wide variety of conditions,” says Spector. “If you’ve got a child with diarrhoea, giving them probiotics will significantly speed up recovery time.” Jane A Foster, associate professor in psychiatry and behavioural neurosciences at McMaster University in Canada, describes the probiotics industry as a “flourishing landscape” and foresees a time when probiotics will be in our orange juice and chocolate bars. But she warns probiotics aren’t always the solution. “The microbiome is partly driven by our own genetics and partly by environmental factors such as stress, diet, age and gender. All these things affect the composition and they probably also affect the function of the bacteria that are there.”

In other words, it’s not simply a cause and effect relationship between the amount of good and bad bacteria in your gut. “The only way bad bacteria’s effects are understood is when we have enough of them to constitute an infection and we have terrible gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhoea (due to E. coli or C. difficile, for example),” explains Spector. “In terms of our gut flora, it’s not yet possible to prove a causal role for any bacteria, as it’s not understood how they all interact in the body. Many of them can’t survive outside the body so we can’t study them in action. The way scientists find out about what bacteria we have is by finding their DNA.”

Happiness is a healthy gut

There are ways that your body can warn you that your gut flora isn’t flourishing. Having IBS can be a sign, along with, says Spector, “being constipated, having a limited diet, feeling bloated; on average, if you’re overweight, unwell and have lots of allergies, you’re going to have poor gut health.” For many, he says, this is the norm and it’s only when you change it and begin to feel better that you realise how bad it was. Your immune system improves and you have fewer colds and infections.

To improve gut health, Spector advises doubling your fibre intake – eating whole foods, such as grains and beans, and plenty of fruits and vegetables. Fermented foods such as yoghurt, sauerkraut and the national pickle of Korea, kimchi, are packed with friendly bacteria. And according to Spector, the number one result so far from the British Gut Project (which has had nearly 6,000 participants) is that the people with the healthiest guts consume the most diverse number of plants. “Whether you’re vegetarian, a carnivore, on the paleo diet or whatever, if you get a range of plants on your plate – be they seeds, nuts, spices, herbs, fruits, vegetables, mushrooms, grains – it’s the variety that’s key.”

Peak gut health corresponds with eating 30 different plant foods each week, and American Gut reports that those in this group were also found to have the least antibiotic-resistant bacteria genes in their guts. The researchers wondered whether this could be because the participants were eating less meat and processed foods tainted with antibiotics. (Unsurprisingly, they found that taking a course of antibiotics within the past month resulted in a less diverse microbiome than in those who hadn’t taken these medicines in the previous year.)

Spector has since launched a second phase of gut research, called the Predict Study, which looks at personal responses to different foods and how this corresponds with the gut flora. The goal is to offer personalised nutritional advice by looking at your gut microbes. Participants in the study, including Spector himself, test their blood glucose levels after consuming everything from bananas to prosecco. The responses, he says, vary widely, even in identical twins, “not because of their genes but because of their microbes.” Frequent glucose spikes are related to an increase in weight and diabetes, and Spector has discovered that these occur in him when he eats bread, whether it’s white or wholemeal. “If I eat pasta or rice,” he says, “I don’t get a spike, whereas other people might have the opposite. It’s the microbes determining that. So if you can find foods that support your glucose levels, then you’re more likely to lose weight long term.”

This is one of the reasons why he believes microbe testing will end up becoming routine. Web-based microbiome testing services are already around £100 he points out, “and as more people use them it’s going to go down to £50. If the NHS did it, the price would be below £20 – the same price as a blood test and instantly more useful.”

Eventually, he says, “I could test your gut microbe and say, based on our database of 10,000 people, whether you should be a rice person rather than a potato person.” One British and American Gut finding already defends alcohol in the ongoing scientific debate over whether any booze can ever be healthy. Happily for moderate drinkers, those who consume alcohol once or more per week have more diverse microbiomes than abstainers. And as the numbers get bigger, more detailed and subtle geographical differences will become clear, along with gut signifiers of disease and the effects of specific diets.

This is an extract from issue 328 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard