The Perseid meteor shower is well underway, making it one of the best times of the year for naked-eye astronomy. This is usually one of the most active meteor showers in the northern hemisphere.

But with the peak of the Perseids coinciding with the full Sturgeon supermoon, conditions in 2022 are not ideal; it's difficult to spot shooting stars with a bright Moon lighting up the night sky. For the best viewing, the ideal time to watch meteor showers is when the sky is as dark as possible, for example on a new Moon, a waxing or waning crescent Moon, or when the moonrise comes after the shower.

But that doesn't necessarily mean you won't be able to spot a Perseid. Read on to find out how to make the best of the Perseids in 2022.

In case you missed it, we've rounded up some of the best Perseid meteor shower pictures from last year. If you're keen to make up for the lack of visible meteors over the next few days, we have a full roundup of this year's meteor showers in our meteor shower calendar, and be sure to check out our astronomy for beginners guide and our UK full Moon calendar to make the most of the night sky.

When is the Perseid meteor shower in 2022?

The Perseid meteor shower in 2022 started on 17 July, and will be visible until 24 August. It peaks on 13 August, with a decent helping of meteors continuing until 16 August, before beginning to wane by around 21-22 August. The best time to view the Perseids will be between midnight and dawn, in this time frame.

"The Perseid meteor shower peaks at 1am in the early hours of Saturday 13 August this year," says astronomy lecturer, Darren Baskill. "That's the moment when the Earth passes through the heart of the stream of dust left behind by Comet Swift-Tuttle."

"From a clear, dark site, a meteor – also called a shooting star – is usually visible every minute or two during the peak hours – and they move quickly!"

In general, Baskill recommends staying up late for the best chance of catching a glimpse of the Perseids.

Can I see Perseids despite the full Moon?

Unfortunately for meteor-watchers, the full Sturgeon supermoon will rise at sunset this evening and peak early in the morning of 12 August. "Its bright glow will overpower all but the brighter shooting stars," Baskill explains.

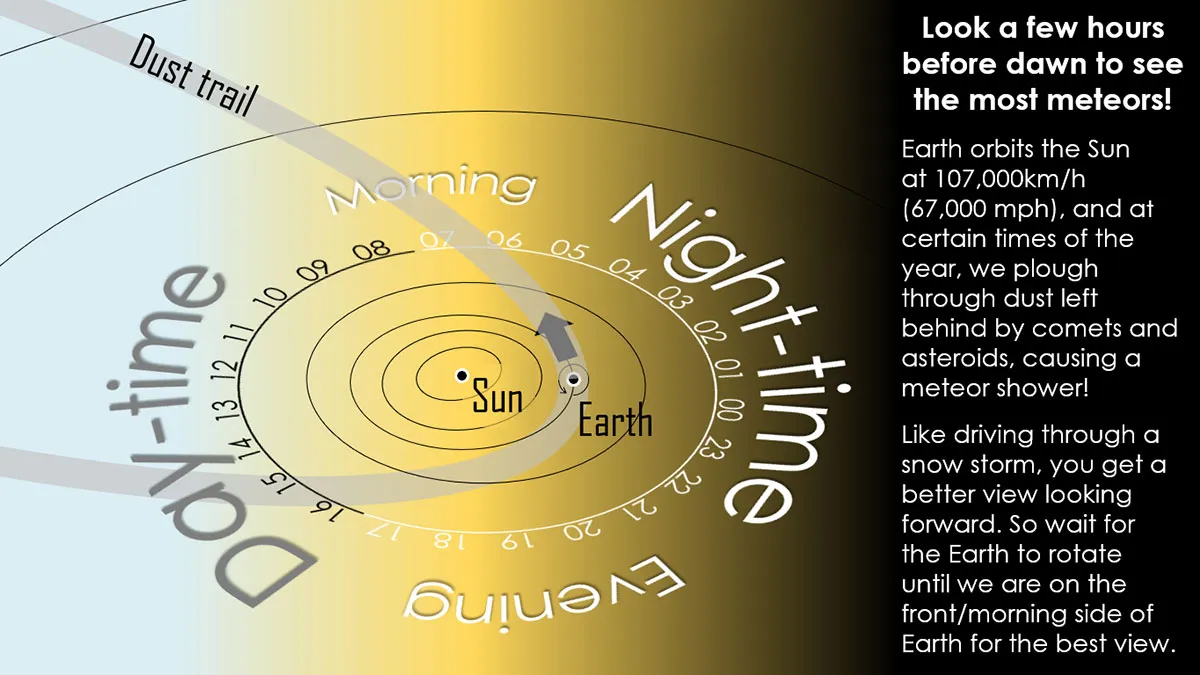

"It's a bit like driving a car through a snowstorm: you get a better view looking forward, as snowflakes hit the car windscreen, than you would looking behind," he says. "And we are on the 'front' of the Earth, as it flies through space orbiting the Sun, at 6am, so you should get a better view in the hours after midnight, weather permitting!"

Although not as easy to spot, stars and satellites are still visible on a full Moon, so all is not lost. Instead of up to around 100 meteors per hour (although realistically this figure is closer to around 25), this year we can expect to see around 10-20 per hour.

How to maximise your chance of spotting a Perseid

Take the opportunity to cool off from the scorching daytime temperatures this year, and get comfortable in a garden lounger, or astronomy chair if you have one. Here's how you can make the best of the Perseids this year:

- Try to avoid city lights, and keep street lights out of your direct line of sight.

- Sit outside and let your eyes adapt for around half an hour, then use a red light filter (essentially a piece of transparent, red material) or a torch with a red filter to help preserve the natural night vision in your eyes.

- Choose a spot where the Moon is obscured. Here in the UK, that's likely to be a position where buildings or foliage blocks out your view of the Moon.

- Watch out for meteor trains. These can linger in the sky for several seconds, and persist after the initial meteor has been and gone.

- Watch out for fireballs. These are exceptionally bright, and it's likely that several people will spot the same one. They are not common, however.

- If all else fails, there will be a lovely view of the last supermoon of 2022...

Where in the sky should I look?

The meteors appear to originate in the constellation of Perseus, hence the name 'Perseid'. At this time of year, in the early morning, look towards the northeast to see Perseus above Taurus the Bull. However, if you're not sure which way that is, you don't need to whip out a star map to work out which way you should be looking.

"These shooting stars could appear anywhere, so it's best just to look directly up, and if you are lucky, you might see a shooting star every few minutes originating from the northeast," Baskill says.

What else can I see?

Try not to feel disappointed at the prospect of not seeing as many Perseids this year. The Draconids and Orionids are just around the corner (October), but if you can't wait that long, there is, of course, still the exciting possibility that you might be able to glimpse a fireball during the Perseids, or a meteor bright enough to defy the glare from the full Moon.

A fireball is an exceptionally bright meteor that can be seen over a wide area, and it's been a rising trend to see fireballs captured by smart doorbells.

Jupiter and Saturn should also be visible in the southern sky, the latter being visible most of the night thanks to its current position opposite the Sun. And, if you're up just before sunrise, you might also be able to see the Morning Star, Venus, as it rises at 4:02am.

What causes the Perseid meteor shower?

The Perseid meteor shower is caused by the Earth's orbit intersecting with the trail of debris left by Comet Swift-Tuttle. Without the glare from the full Moon, this results in hundreds (or thousands) of bright trails which appear to radiate from the direction of the constellation Perseus.

Comet Swift-Tuttle is a large snowball comet, comprised of dust, ice and rock. Its nucleus has a diameter of 26km (16 miles) and it takes 133 years to orbit the Sun, making it a short-period comet. Its official designation is 109P/Swift-Tuttle, the 'P' indicating that it is a periodic comet. Comet Swift-Tuttle was last visible to us in 1992, but won't pass our way again until 2125.

- Read more about different types of space rocks

Do I need any equipment to watch the meteor shower?

No, you don't need a telescope or even binoculars to watch a meteor shower. In fact, unlike most other astronomy, you're better off without them.

When you're looking at a planet, full Moon or star, your object of interest will move very slowly across the sky. That means you can set up your telescope to point in the right direction, and then gradually adjust it as the night goes on and the Earth spins.

However, meteors are called 'shooting stars' for a reason: they zip across the sky in a bright flash, and then they're gone. While we know the area of the sky where the meteor shower originates, we won't know where any one in particular will appear. So, you're better off with a much broader field of vision.

The best equipment you can use is a lawn chair, or another reclining chair you can take outside. You might also want a blanket or a thermos of something hot if it's going to be a cool night.

Find a spot outside with as little light pollution as possible, and lie back so you can see as much of the sky as you can. Then, you should let your eyes adjust for up to 20 minutes without any other light sources – including your phone. As your night vision improves, you should start to see more and more in the sky.

About our expert, Dr Darren Baskill

Dr Darren Baskill is an outreach officer and lecturer in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Sussex. He previously lectured at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, where he also initiated the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition.

Read more about meteors: