School's out, the evenings are mild, and with nightfall coming fractionally earlier every day you may have already caught a few meteors streaking across the sky from the long meteor shower, the Perseids. The shower continues until around 24 August and if you’re lucky, you (or your video doorbell) might even be able to see a fireball.

For the UK, the Summer Triangle is a familiar feature of the summer skies, with the blue-white star Vega in Lyra the Lyre the first to make its appearance as darkness descends. To the east, in the constellation Cygnus the Swan, you can see the blue-white supergiant Deneb, the second star of the Summer Triangle. The third is the fast-spinning star Altair, in the constellation Aquila the Eagle.

August has welcomed the third, and last, supermoon of the year, and in case you missed it, we've put together a gallery of the best Sturgeon supermoon pictures from last night.

If you’re enjoying the warm weather and clear nights, why not plan ahead with ourfull Moon UK calendarandastronomy for beginners guide? And in case you missed it, check out our round-up of the best Buck Supermoon pictures from last month.

When can I see the Sturgeon supermoon 2022?

The Sturgeon supermoon was visible last night Thursday 11 August 2022 and into the early hours of this morning, in the UK and around the world. If you were unable to see August’s supermoon at its peak, it will also appear full tonight.

Last night, the Moon was in the zodiac constellation of Capricornus, a faint constellation in the southern sky. Our nearest celestial neighbour was visible 3.9° south of Saturn, staying relatively close to the planets throughout the month. On 15 August, it will pass 1.9° south of Jupiter, then on 18 August, the Moon will be 0.6° north of Uranus, in the constellation Aries. On 19 August, we’ll be able to see the Moon in the constellation Taurus, 2.7° north of Mars before passing 4.3° north of Venus on 25 August.

If there happens to be rain (which is looking unlikely for tonight - but we may be in with a chance on Monday) or you're near another water source (such as a waterfall) keep your eyes peeled for the super rare night sky phenomenon, a moonbow.

What is the best time to see the Sturgeon supermoon?

The full Sturgeon supermoon rose at 8:55pm in the southeast last night, Thursday 11 August 2022 (as seen from London, UK). The Sun began to set at 8:30pm, and the Moon rose in the still-twilight sky. We were offered a stunning view, and it was possibly the best full Moon of the year. You'll be able to see it again tonight, and here in Bristol, conditions still look clear, so the Moon should look bright against the gradually darkening sky.

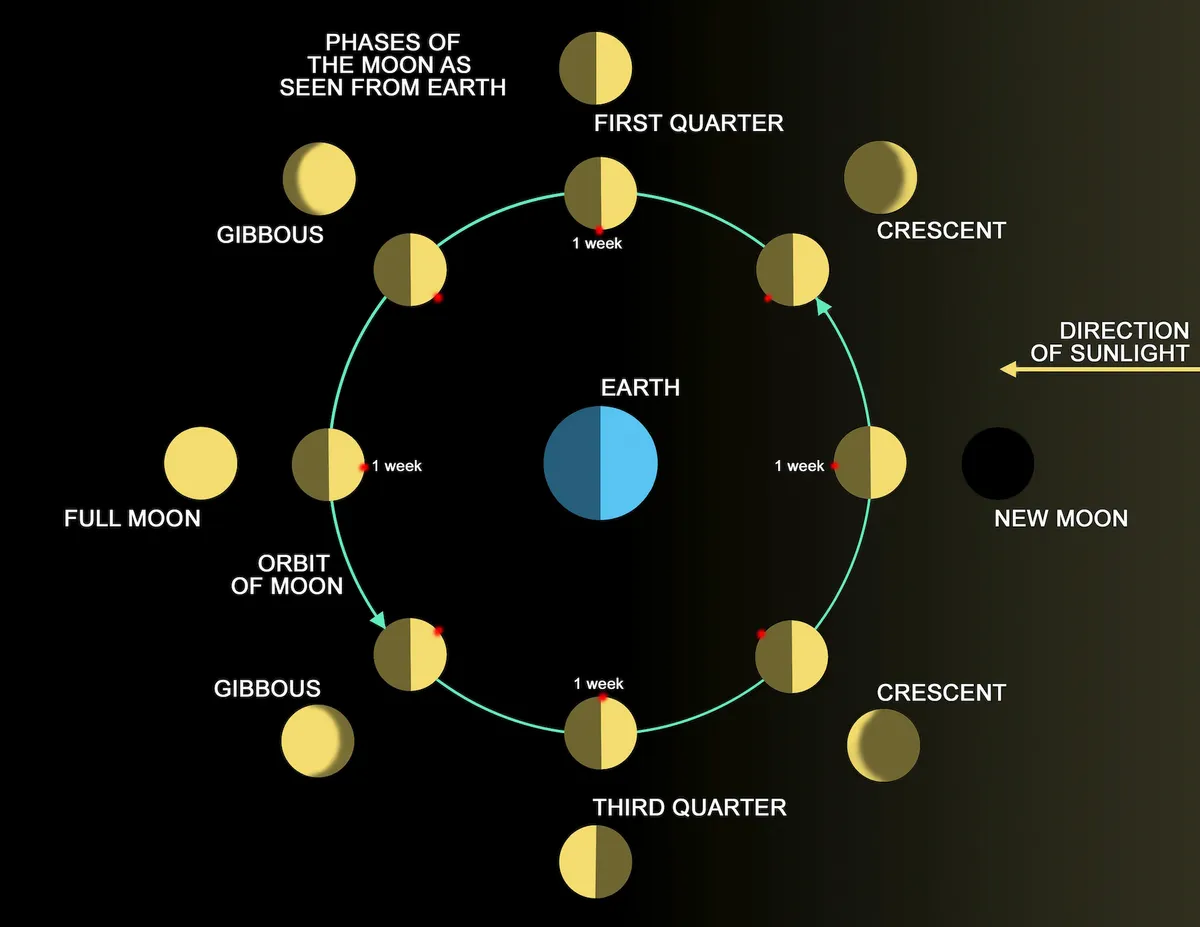

The supermoon reached its peak at 2:36am this morning, 12 August 2022. This specific moment has a name, syzygy, and it's the name given to a configuration that occurs for just a moment, when the Earth is directlybetween the Sun and the Moon, in a straight line (see below for a diagram).

As the Moon rises, it will keep pace with Saturn in the sky, with Vesta (the brightest asteroid in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter) loitering nearby.

If you live in an area where the horizon is obstructed (for example, by buildings or trees), then it’s recommended you wait a little longer, until the Moon has risen higher in the sky at around midnight.

The Moon reached peak illumination at 2:36am last night. Although it was very difficult to discern the minute difference with human eyes, the bright Sturgeon supermoon flooded the dark sky with light; apologies to everyone hoping to see the Perseid meteor shower.

As an aside, if you’re interested in seeing Vesta through binoculars, the best time to see it will be on the 22 August, when the asteroid is at opposition.

What colour will the Moon be tonight?

If you saw the Moon rise last night, you might have noticed a reddy-yellow hue while it was still low to the horizon. The same is set to happen tonight, and for a few hours after moonrise, the supermoon will take on a stronger colour. But why is this?

It's all down to the atmosphere. This layer of gases that envelop our planet scatter sunlight in a process known as Rayleigh scattering. Light travels in waves, with each colour in the light spectrum having a different wavelength. This means that the different colours get scattered differently. The more atmosphere, the more of the shorter wavelengths get scattered, leaving behind those colours with longer wavelengths.

When the Moon is low on the horizon, you're looking through more of the atmosphere, and light has a longer distance to travel. Those colours with shorter wavelengths, like blue, get scattered leaving behind those colours with longer wavelengths like red, orange and yellow. As the Moon rises higher in the sky, less of the blue light gets scattered and the Moon takes on a more familiar greyish-white hue.

Why is it called the Sturgeon Moon?

The Algonquin tribes of North America named August’s full Moon after the abundance of sturgeon in the rivers and lakes at this time of year. The sturgeon is North America’s largest freshwater fish and have been reported to reach lengths of up to 6m (15-20 feet), and weighing nearly a tonne. Although once plentiful, they are now endangered.

In Old English, the Sturgeon Moon was sometimes known as the Barley Moon, Fruit Moon, or Grain Moon. Some members of the Inuit named the August full Moon after the young swans taking flight at this time, the Swan Flight Moon. In China, August’s full Moon marks the start of the Hungry Ghost Festival, a traditional festival where ancestors are honoured, and ghosts appeased.

Is the Sturgeon Moon 2022 a supermoon?

Yes, August's full Moon, the Sturgeon Moon in 2022 is a supermoon, and the third (and last) supermoon of the year!

Supermoons are categorised when the Moon is at 360,000km or less away from Earth in its orbital path, and we'll often have two or three full supermoons in a row. In 2022, the June full Moon, the Strawberry Moon and the July full Moon, the Buck Moon were also supermoons.

What causes a supermoon?

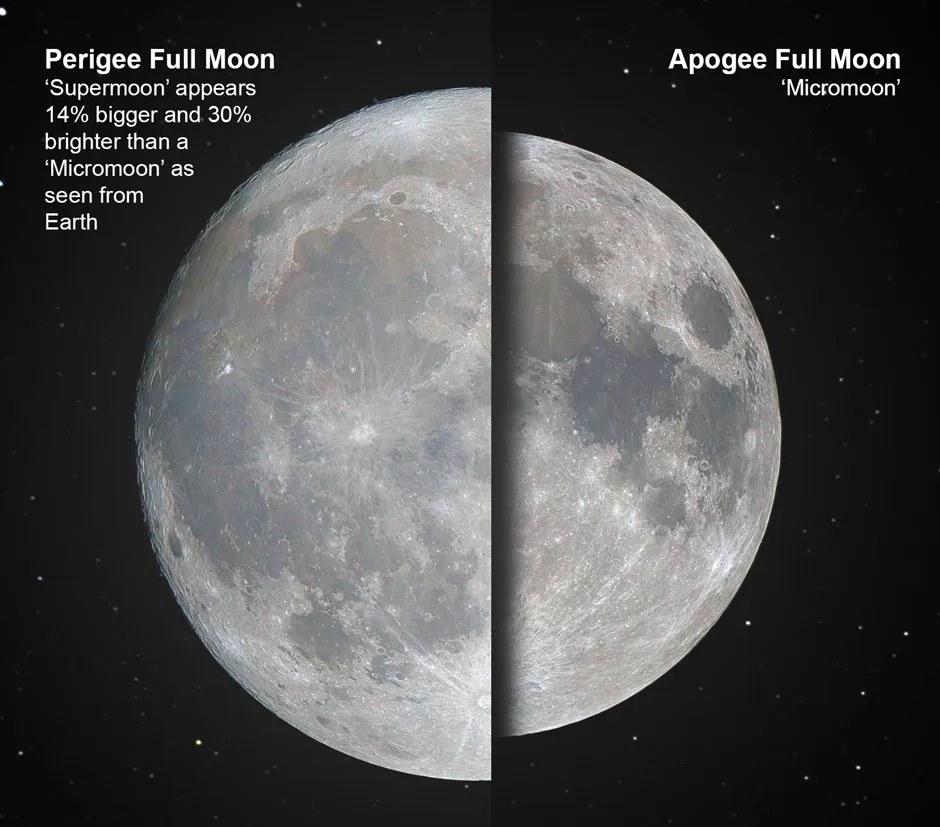

A supermoon appears around 7 per cent larger and 15 per cent brighter than a standard full Moon, or 14 per cent bigger and 30 per cent brighter than a micromoon. This effect is amplified further when the Moon is still low on the horizon, thanks to the Moon illusion.

A supermoon occurs when the Moon, which orbits the Earth in an elliptical (oval-shaped) orbit, is at its closest point to Earth along this orbital path. This point is called the perigee. When the Moon reaches perigee at the same time as a full Moon occurs in the lunar cycle, the Moon looms larger in the sky and we get a supermoon.

Conversely, when a full Moon is at its furthest distance in its orbital path around the Earth (called the apogee), the Moon appears smaller. Rather aptly, this is termed a micromoon.

How does a supermoon affect tides?

We know what you’re thinking: surely a Moon that close to Earth will have some major impact on our tides? However, you needn’t worry.

“It’s true that about two-thirds of tides are influenced by the Moon's gravity (and a third the Sun). We get high tides when the Sun and Moon are aligned – at a full or new Moon,” explains astronomy lecturer Darren Baskill.

A full Moon makes the high and low tides more extreme, and thanks to the Moon making its closest approach to Earth, a supermoon has a greater effect still. However, the highest tides tend to follow the supermoon by a couple of days, and to the casual observer, the effect is subtle.

“As the supermoon will be closer to Earth than a normal full Moon, it will have a greater tidal force – but this will only change the tide by a few centimetres.”

However, there are some studies that do suggest a supermoon increases the risk of more severe beach erosion near the shoreline. After 25 years of gathering data, scientists in Japan have suggested that supermoons drive more erosion of the sand in the swash zone, which is the part of the beach where waves crash after breaking. More research is needed to determine the interplay of high waves and storm surges with these findings.

How often do we get a full Moon?

The lunar cycle occurs over a period of 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes, and 3 seconds, usually rounded to 29.53 days. That means we get a full Moon every 29.53 days. This is calculated by the time it takes the Moon to orbit the Earth once, as measured from new Moon to new Moon. This is also known as one synodic month.

We usually have 12 full Moons in a calendar year, occurring when the Moon is fully illuminated by the Sun. This happens when the Earth is located directly between the Sun and the Moon.

However, because one lunar cycle takes a littleunder a calendar month in our Gregorian calendar, we sometimes have 13 full Moons in a year. This occurs around every two to three years. This means that we will see two full Moons in a single month, and this extra full Moon is known as a ‘blue Moon’. The next blue Moon will occur 30-31 August 2023.

Similarly, we sometimes get two new Moons in a month, and this extra new Moon is known as aBlack Moon. The most recent Black Moon was 30 April 2022, and the next will be next year, 19 May 2023.

About our expert, Dr Darren Baskill

Dr Baskill is an outreach officer and lecturer in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Sussex. He previously lectured at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, where he also initiated the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition.

Read more about the Moon: