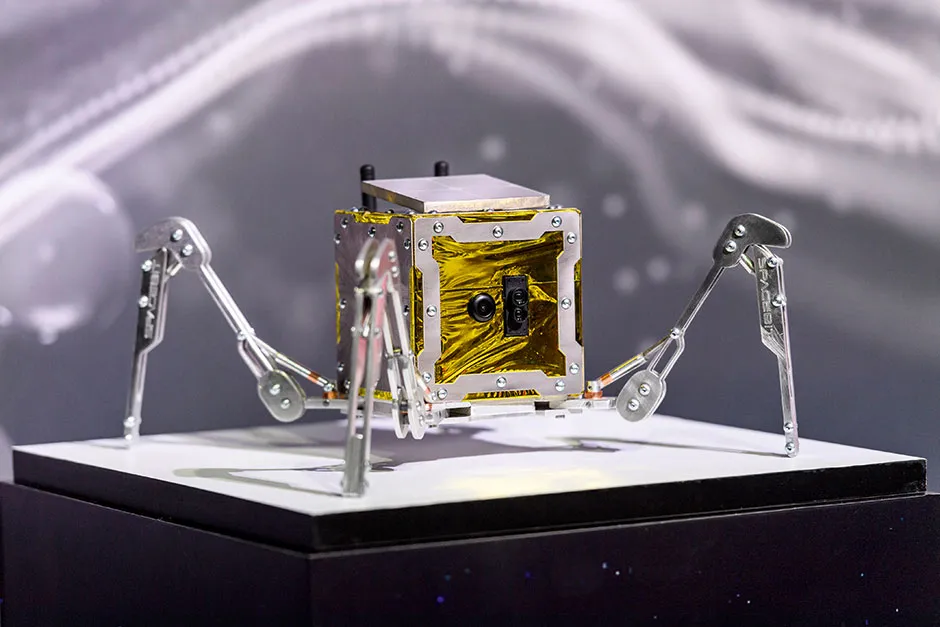

In the middle of 2021, a small robotic spider may be taking its first tentative steps on the Moon. It’s not exactly The Spiders From Mars, but the late David Bowie will have played a part in getting it there.

Pavlo Tanasyuk, CEO and founder of the British company Spacebit, remembers once listening to David Bowie’s The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars and wondering about one day building rovers with legs rather than wheels.

The idea lay dormant until Tanasyuk was visiting a friend at the Japan Aerospace Agency (JAXA), and mentioned his long-held idea of a spider robot on Mars or the Moon. The friend responded immediately with the Japanese proverb of the asagumo, the morning spider who brings fortune.

Read more about missions to the Moon:

“That’s when it clicked and I decided that we actually should be doing this rover,” says Tanasyuk.

He incorporated the UK company Spacebit to begin developing the asagumo spider robot. Launch is now scheduled for July 2021, onboard the Peregrine lander that has been developed by the private American company Astrobotic. Peregrine will be flown on a Vulcan Centaur rocket, and if all goes to plan, asagumo will be the UK’s first lunar lander.

Walking on the Moon is tricky because of the regolith, which is the layer of rock fragments and dust that covers the lunar surface. For a walking rover the dangers are two-fold.

First, the legs can sink into this layer, impeding the movement. Second, the dust and fragments can get into the articulated parts of the legs and the motors, causing them to cease up.

To overcome the first problem, Spacebit is designing the legs to look more like ski poles, which have pads on the end to stop them disappearing beneath the surface. As for the second, it is a risk that the team are willing to take because they don’t want their rover to walk on the surface indefinitely, just long enough to get to their real target: a lunar lava tube.

Exploring ancient lava tubes

A lava tube is a natural tunnel formed by rivers of lava flowing away from a volcano. The top of the flow is exposed to the cooling air, and gradually hardens to solid rock, forming a roof over the lava flow.

When the lava has all drained away it leaves an empty lava tube. Since the Moon was once volcanically active, there are thought to be an abundance of lava tubes there.

Inside a lava tube, there is much less dust but more rocks, so legs are actually better suited to clambering over obstacles.

We are world-leading in the area of cosmochemistry

Sue Horne

“We already did tests in the lava tubes of Mount Fuji in Japan. I went inside the lava tube with the rover, and we tested how it walks. Basically we can see that the legs are better suited for the lava tubes than wheels [as legs let the robot clamber over obstacles],” says Tanasyuk.

There are some lava tubes in the vicinity of the Peregrine lander’s touchdown area, and one of these will be the first target for the asagumo. The reason for the interest in lava tubes is that human bases may one day be constructed inside these natural rock formations.

While Spacebit may be sending the UK’s first Moon lander, it is far from the only UK space mission that is currently in development. Indeed, it is just the tip of the lunar iceberg...

The UK in space

The UK’s lunar expertise has been built up since the days of NASA’s Apollo missions, which took astronauts to the Moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Planetary scientists Grenville Turner and Colin Pillinger were two pioneers of UK space science. They were held in such high esteem that they were granted access to the lunar rocks that the American Apollo astronauts brought back to Earth.

This was an accolade in itself. “You had to be the best of the field to actually get access to these samples,” says Sue Horne, head of space exploration at the UK Space Agency. She adds that Pillinger and Turner were “wizards at instrumentation”.

Together, the pair established the UK’s excellence in the area of cosmochemistry, analysing samples not just from the Moon but from meteorites, some of which are now thought to have come from Mars. They also trained many students over the years who themselves have gone on to successful science careers, training more people in the process.

“We are world-leading in the area of cosmochemistry,” says Horne. As a result, the UK now routinely supplies key instruments for various science missions carried out by the European Space Agency (ESA).

These include the comet-chasing mission Rosetta, the recently launched Solar Orbiter, and the forthcoming JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE). By supplying instruments and expertise, the UK’s scientists gain full access to the mission. “By working with Europe, we can do a lot more than we can afford individually,” says Horne.

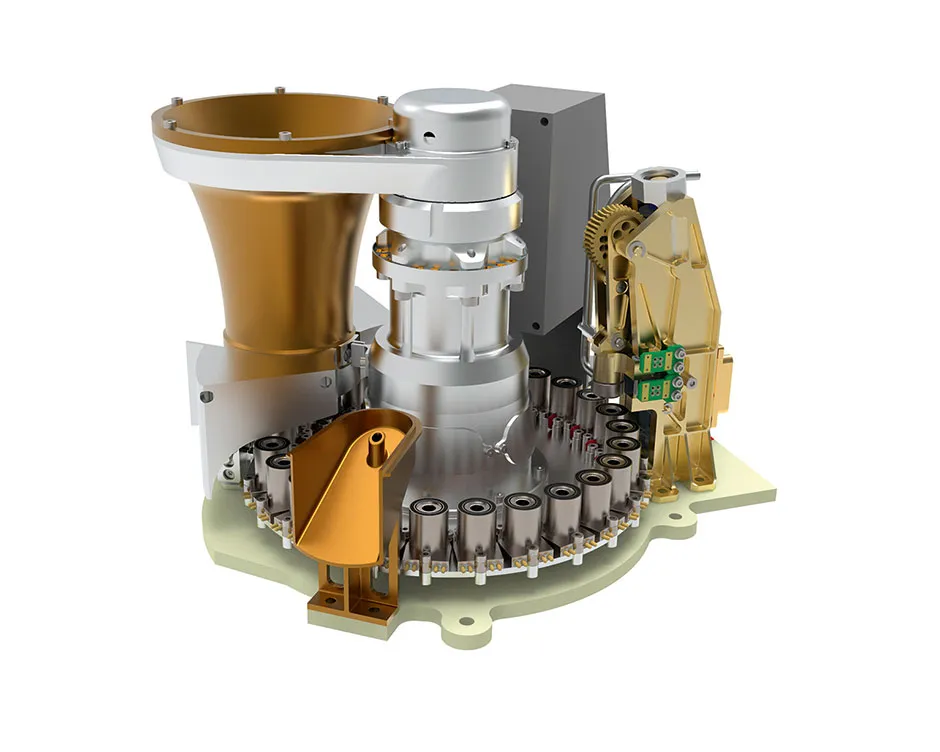

The collaboration is set to continue in the future. For example, the Open University is developing a miniature chemical analysis laboratory for ESA. Called ProSPA, the lab will fly on the joint Russian-ESA Lunar Resource Lander mission (Luna 27) in 2025.

The company MDA UK is also working on the same mission, building a vital component of the autonomous landing system, a LiDAR to measure the distance to the ground.

And the UK’s ambitions do not stop there.

Deep space communications

Beyond science, Horne and her colleagues have identified an emerging need in space exploration: deep space communications. This may not sound glamorous, but it is going to become increasingly important as more and more people send spacecraft to the Moon.

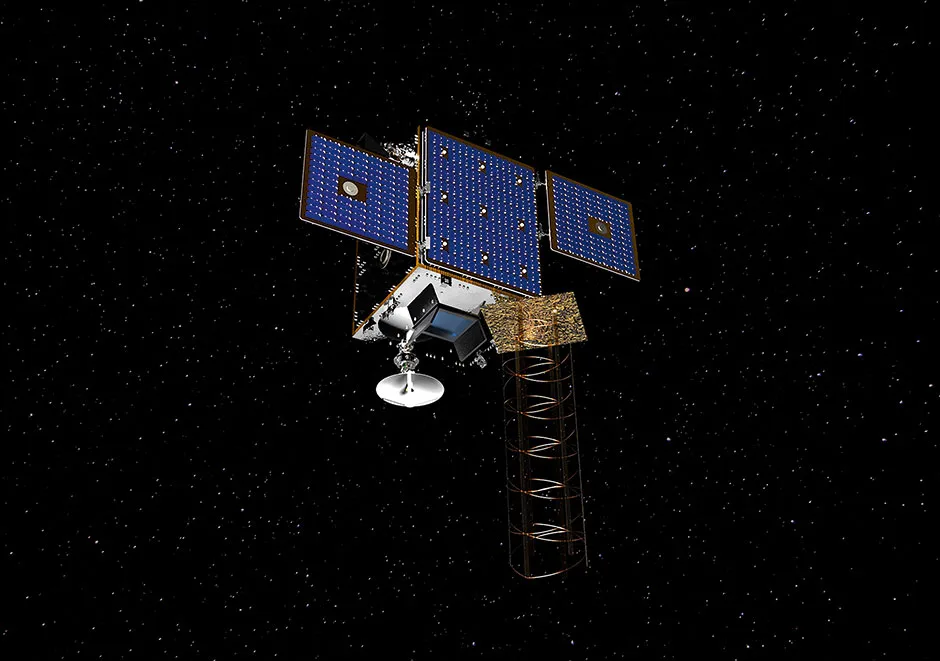

In the past, virtually every lunar mission has had to carry a transmitter powerful enough to beam signals back to Earth. Now, however, the UK is building a dedicated communications satellite to orbit the Moon.

Called the Lunar Pathfinder, it will relay signals back to Earth, meaning that landers, rovers and other orbiters no longer need to carry the expensive, bulky pieces of kit that were once needed.

ESA has funded the Pathfinder, which is being made by Surrey Satellite Technology Limited (SSTL), in Guildford. ESA will also be the Pathfinder’s first customer.

Pathfinder is scheduled for launch in 2023. Once it’s up and running, the next step being considered by ESA is a constellation of satellites around the Moon that can also provide the lunar equivalent of GPS.

“The idea is to have a number of satellites that will allow enhanced communications coverage of the Moon and high reliability navigation services,” says Nelly Offord, the business line manager for exploration and head of lunar services at SSTL.

Of course, it’s all well and good providing a satellite that can beam messages back from the Moon, but you then need a ground station to receive them. This is where the once defunct Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station in Cornwall comes in.

Situated on the Lizard peninsula on the southern coast of Cornwall, Goonhilly was established in 1962 to receive signals from the experimental telecommunications satellite Telstar. Over the ensuing decades, the site grew into the world’s largest satellite ground station before gradually becoming obsolete.

In 2011, the rebirth began when a private company named Goonhilly Earth Station Limited leased the site from British Telecom and began to refurbish the antennas.

Now, almost a decade later, the site has attracted money from the Cornwall Local Enterprise Partnership fund and from ESA to help with the upgrading of the antennas, which were in a rather sorry state.

“One antenna had a tree growing through it,” says Matthew Cosby, Goonhilly’s director of space engineering.

Now, Goonhilly is poised to provide additional coverage for ESA’s deep-space tracking system, called ESTRACK. In particular, the Cornish site will be receiving data from some of ESA’s older missions, such as Integral, Gaia and Mars Express. It will also be the ground station for SSTL’s Lunar Pathfinder.

World leaders in space tech

Beyond ESA, there could also be another big customer on the horizon. It is no secret that the US is pushing hard to get back to the lunar surface. With the Artemis programme, the White House has set NASA a deadline of 2024 to have boots on the Moon.

This represents a considerable acceleration of the more realistic goal to land by 2028, and it is clear that not even NASA has the money or the workforce to make it happen by itself. While NASA is turning to US industry for help, particularly in building lunar landers, the space agency is going to have to turn to international partnerships to get other things done.

Offord thinks that providing reliable high-quality communications is one area in which ESA and the UK could help. “NASA is very interested in using our services, and ESA is right now talking to them about which missions we could support,” says Offord.

To stay ahead of this particular curve, Cosby is the UK’s representative on the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS). This is where the standards for spaceflight communications are discussed and agreed, including the communications protocols for NASA’s 2024 lunar landing.

Everything he learns is implemented at Goonhilly and across the UK, so that if the call comes, they will be ready to jump straight in and relay those historic images – just as Goonhilly was used back in the 1970s to relay images and data from the original Apollo Moon landings.

Although NASA and ESA are the only real customers in town at the moment, it may not be long before private companies are looking to buy communications services too.

Read more about the Moon:

- The origin of the Moon: how it formed and how we found out

- Entire surface of the Moon mapped for the first time

- What if we mined the Moon?

Take Tanasyuk’s Spacebit: next year’s mission with the spider robot is just the first of a rolling programme of increasingly complex missions for the asagumo. Depending on where they touch down, the first mission may or may not reach a lava tube.

Instead, the asagumo will be used to demonstrate the spider robot technology. “It will take selfies, do some science and distribute the data to schools and universities for free,” says Tanasyuk.

It is a time-limited mission, however. Asagumo is solar-powered and when the Sun sets on the Moon, it takes a fortnight to reappear. In that time, the tiny asagumo, which can fit into the palm of a hand, will have frozen forever. So the first mission will only last about one week.

The objective is to take humans to Mars. But to do that, we need to use the Moon as a testbed

Sue Horne

For their second mission, Spacebit is designing a carrier, into which a number of asagumo will be able to climb. The mothership will be much larger and able to sustain the spider robots for the duration of the lunar night. At dawn, they will crawl back outside and continue their exploration.

If all goes well, for Spacebit’s third mission, the carrier will be taken from orbit to the lunar surface on a lander of the company’s own making. And this is really where Spacebit’s future lies.

“We are the only company not only in the UK, but in the whole European region to be designing and working on a lunar lander,” says Tanasyuk. The idea is to corner at least part of the lunar transportation market.

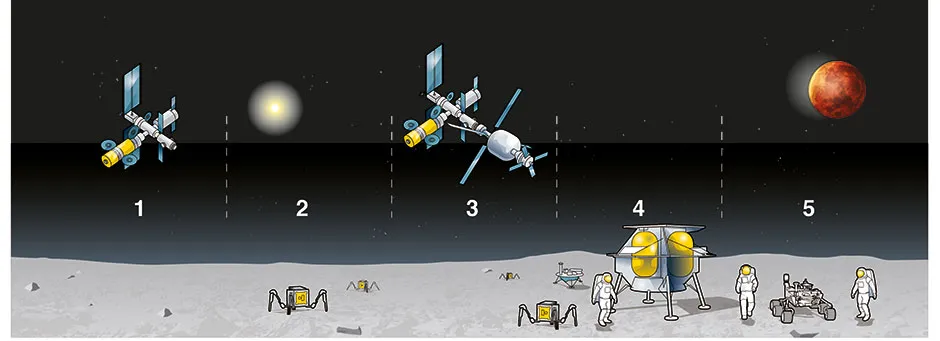

There can be no doubt that through the coordination of the UK Space Agency, companies and organisations across the UK are positioning themselves to play key roles in returning humans to the Moon. And as exciting as that is, Horne makes it clear it is also a dress rehearsal for something much larger: human missions to Mars.

“The long term objective is to take humans to Mars. But to do that, we need to use the Moon as a testbed. We need to test out technologies and capabilities,” says Horne.

In the 1960s, the UK flirted with the idea of becoming a space-faring country. It built the Black Arrow rocket and launched the Prospero satellite into low-Earth orbit. Then the country turned its back on the endeavour.

Now it appears that there is a renaissance of interest in space in the UK. And with companies like Spacebit, SSTL and Goonhilly Earth Station Limited, it seems there is no shortage of individuals and organisations ready to accept the challenge.

- This article first appeared in issue 352 ofBBC Science Focus–find out how to subscribe here

From the Moon to Mars

The new exploration of the Moon is a test of techniques and technology for the larger international endeavour of going to Mars.

While it is difficult to put absolute timescales on this endeavour because budgets are being worked out as each country goes along, it is possible to say roughly what the stages will be before humankind is ready to launch a Mars mission.

- First missions test landing and ascent capability on the Moon

- More missions extend the range of tasks performed on the lunar surface

- The lunar station is extended to allow more astronauts to live and work around the Moon

- A permanent lunar habitat is established, allowing longer stays on the surface

- Extended stays on the lunar surface or between nine months and a year begin to reach the time needed for a mission to Mars