Picture the scene. After a routine blood test, you visit your GP for the results. “It’s all good,” says the doctor reassuringly. “The only problem is that you’re getting older.” Then, with a flourish of the prescription pad, the doctor adds: “But I can help you with that. Take these tablets. They’ll slow the ageing process and help you to stay healthy. Oh, and they might just make you live longer too."

A drug that extends your life, slows ageing and staves off the ravages of old age, including frailty and disease? It sounds too good to be true, and yet, an increasing weight of evidence suggests not just that these drugs are within reach, but that they may already be here.

Some can be found on the shelves at your local health store, while others are drugs for conditions such as diabetes and cancer that are being repurposed. Animal studies have demonstrated their potential, and now clinical trials are beginning to assess if their promise holds true in humans. If it does, those who are middle-aged now could become the first generation to benefit from their use. Imagine an 80-year-old with the biology and ‘get up and go’ of someone 30 years younger. How joyful not to have to act your age!

Read more about ageing:

- The race to stop ageing: 10 breakthroughs that will help us grow old healthily

- Instant Genius Podcast: The science of ageing, with Dr Andrew Steele

- Forever young: Senescent cells and secret to stopping ageing

Live better for longer

In the last couple of decades, the science of anti-ageing has moved from science-fiction into academically rigorous, evidence-based, peer-reviewed science. It’s not about achieving immortality, having your brain cryogenically preserved or any of the other outlandish propositions that have been mooted.

“There are a lot of people out there who sell you snake oil and tell you that you’ll live forever, and then when you die, nobody sues them,” says Dr Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Ageing at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. Instead, it’s about improving what scientists call the ‘healthspan’, or the number of years that people can live well without disease. Extending the lifespan could be a fortuitous side effect, as could the ramifications for the economy.

Currently, 80 per cent of the world’s adults aged 65 or over have at least one chronic illness, while 68 per cent have two or more. The human suffering is huge, and in the next 30 years, the number of over-65-year-olds is projected to double to 1.5 billion. This will be costly.

“If we had a drug that adds even one or two healthy years onto the lifespan, it would have trillions of dollars of effect on the world economy, because people would be productive for longer and they wouldn’t have all these morbidities that cost our healthcare systems so much,” says Jim Mellon, chairman of the longevity company Juvenescence.

It’s no coincidence that age is the biggest risk factor for illnesses such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and neurodegeneration. The ageing process involves a whole raft of biological changes that drives their development. Scientists call these changes ‘hallmarks’ and around nine have been identified, including the accumulation of genetic mutations, the unravelling of chromosomes and the impaired ability of tiny cellular power packs, called mitochondria, to function.

According to the theory, if you can correct these problems, you won’t just slow down ageing, you’ll also prevent or defer many of the diseases that are associated with old age.

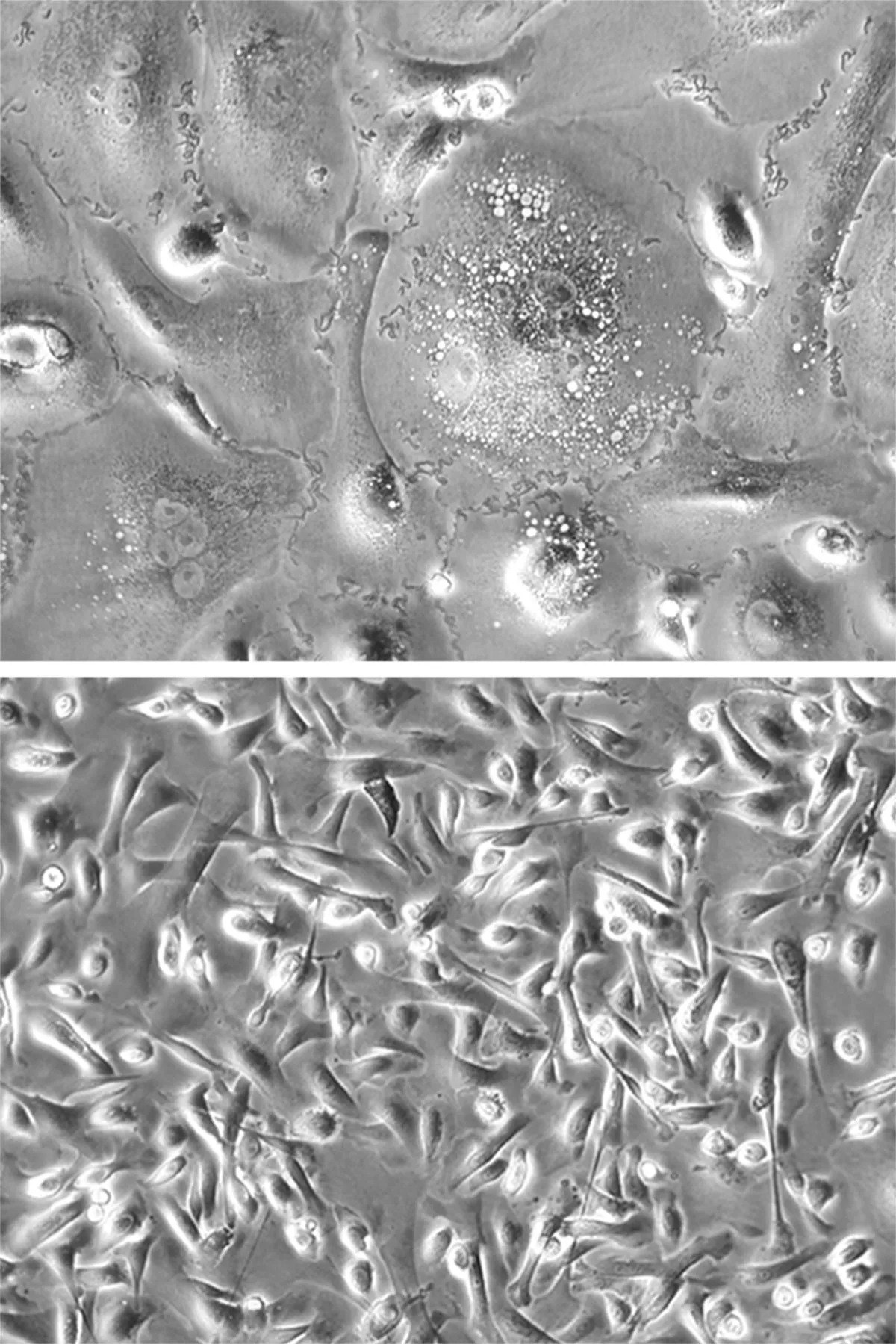

In December 2021, researchers from the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai revealed that a natural compound found in grape seeds could prolong the lifespan of old mice by 9 per cent, and make them physically fitter too. The compound, called procyanidin C1, works by targeting another of the hallmarks of ageing: the build-up of tired, worn-out cells that are described as ‘senescent'.

In our younger years, the immune system clears senescent cells from the body before they can cause a problem, but as we age and our immune system falters, the cells get to hang around, secreting inflammatory molecules that injure the surrounding tissue.

“It’s like a fire that spreads,” says Ming Xu, who studies senescence at the University of Connecticut’s Centre on Ageing. “It’s a very small population of cells, but they have a very large and very damaging effect.” Drugs that seek out and kill these senescent cells, known as senolytics, are among the most promising anti-ageing therapies.

Xu and colleagues have shown that when small numbers of senescent cells are transplanted into mice, it ages them. Then when the same mice are treated, not with procyanidin C1, but with a cocktail of two different senolytic drugs, the rogue cells are destroyed and the mice become more robust. They develop stronger muscles, become more active and live longer. The same results are seen in mice that have aged naturally.

It’s all the more impressive because the mice received the drugs very late in life, when they were already two years old. “It’s the equivalent of a person beginning treatment when they are 70 or 80, and then having their healthy lifespan extended by five to six years,” says Xu.

Also encouraging is the fact that these drugs are already known to be safe for human use. Quercetin, which is a plant pigment found in many fruits and vegetables, is sold as a dietary supplement, while dasatinib is approved for use as a blood cancer drug.

Further animal studies have shown that senolytic drugs can delay, prevent or ease more than 40 diseases, including cancers and various disorders of the heart, liver, kidney, lung, eye and brain. Preliminary studies in humans show that they reduce the number of senescent cells, curb inflammation and alleviate frailty, and now dozens of clinical trials are underway to assesstheir impact on various conditions, including diabetes, arthritis and Alzheimer’s disease.

All of these trials will yield vital information, but if a senolytic or any other drug is ever to be used as a genuine anti-ageing therapy, it’ll need to pass muster in the human equivalent of Xu’s mouse study. As well as testing these drugs in people who already have disease – as is happening in the current clinical trials – they also need to be rigorously tested in healthy people who are ageing naturally.

Speeding up a slow process

It’s a conceptual no-brainer and should be straightforward, save for a couple of problems. The first is that humans take decades to age, a predicament that makes the requisite trials both lengthy and expensive.

One potential solution to this problem, currently under investigation, is to use molecular proxies or ‘biomarkers’ of the ageing process. These are subtle changes, such as the addition of certain chemical groups to DNA, that occur across smaller time frames and are thought to be indicative of the broader ageing picture.

Another option is to turn to man’s best friend. Dogs age around seven times faster than humans, and experience many of the same age-related diseases and declines. They also share our homes and many of the same environmental influences that contribute to ageing. In short, they’re an excellent model of the ageing process, and are willing to help out in exchange for treats and belly rubs.

As part of the Dog Aging Project in the US, 500 canines are helping to assess the worth of another putative anti-ageing treatment, called rapamycin. Rapamycin also targets senescent cells, as well as several of the other hallmarks of ageing.

Relatively large doses are given to transplant patients to help prevent organ rejection, but in small doses it’s been shown to prolong life in yeast, worms, flies and mice. The dogs will be followed for up to a decade and if rapamycin’s promise holds true, those who receive the therapy could have their lives extended by up to four human years (or 28 dog years).

The second problem with arranging the requisite human studies is less practical and more attitudinal. According to the current medical paradigm, ageing is not something that needs to be treated. Along with hangovers and nuisance phone calls, ageing is viewed as a grim inevitability of life.

If the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other medical regulators are ever to approve a drug for ageing, they would first need to recognise that ageing is a preventable condition that can be targeted therapeutically. “We don’t want to call ageing a disease,” says Barzilai. “The people we want to help don’t want us to call them sick, but ageing does need to be officially recognised as an ‘indication’ that is treatable.”

So Barzilai has found a way around the conundrum. His focus is on another potential anti-ageing drug, called metformin. Metformin is a cheap and successful medicine. Every day, millions of people take it to control their type 2 diabetes, but in 2016, Barzilai suggested it could be used to slow ageing.

Key to his argument is a 2014 UK clinical trial involving over 150,000 people, which revealed that diabetics taking metformin live longer than non-diabetics who don’t, and a growing number of separate studies that demonstrate metformin’s ability to prevent specific age-related disorders. Taken together, these studies hint that metformin may be able to improve the healthspan, but they don’t quite nail it. What’s needed is a clinical trial that ties all these loose ends together in a single, well-designed study. Enter, the ‘Targeting Aging with Metformin’ (TAME) trial.

Barzilai and colleagues are recruiting 3,000 adults, aged 65 to 80, who don’t have diabetes, to receive either metformin or a placebo over a four-year period. During this time, the team will monitor age-related biomarkers and the time it takes for each of the patients to develop a major age-related disease, such as dementia or stroke.

Instead of looking at the ability of metformin to delay a single age-related disease, as the other trials have done, this study will assess the drug’s capacity to delay the onset of age-related disease in general. It will show if metformin can increase the healthspan.

If the trial succeeds, its effects could be far-reaching. TAME has the power to prove that ageing really is something that can be targeted and treated with drugs. This, in itself, will be a major paradigm shift. “We hope it will inspire the FDA to make ageing an indication and provide a template for other biotech companies to do similar studies,” says Barzilai.

While other scientists pursue different anti-ageing strategies, such as gene therapy or tissue transplants, taking tablets is so much simpler. Metformin could become the first authorised anti-ageing drug with the ability to not just prolong life, but to prolong a healthy life. Then after metformin, other anti-ageing drugs could follow. Instead of treating each age-related medical condition separately, as currently happens, it’s possible to imagine a future where these conditions are ‘treated’ together, by targeting multiple hallmarks of ageing.

Just as statins are doled out today to lower cholesterol, and prevent strokes and heart disease, so too anti-ageing medicines or ‘gerotherapeutics’ could be prescribed to prevent the diseases of old age. Based on the results of a blood test, which could indicate how fast you’re ageing and which diseases you’re prone to, a clinician might prescribe one or more anti-ageing drugs.

Metformin, rapamycin, quercetin, dasatinib and other as-yet-unidentified anti-ageing drugs could all be part of the picture. It would mark a shift away from the prevailing medical model, where diseases are treated reactively after symptoms have occurred and suffering has set in, to a preventative model of care, where patients are monitored proactively and future diseases are averted.

With a handful of promising anti-ageing drugs already in existence, ageing has never looked so ‘treatable’, and yet, there’s just one final problem. Clinical trials don’t come cheap, so the question is, who pays?

Government funding agencies seemingly aren’t keen to invest in the anti-ageing area. Regulators don’t tend to fund studies of drugs that are already on the market, and the pharmaceutical industry won’t cough up for trials of drugs that are generic, cheap or off-patent, with no profit margin.

The 30 or so bona fide anti-ageing companies that exist are more interested in developing their own proprietary therapies than readily accessible drugs such as metformin or quercetin. Until additional funding can be found, this means that safe, affordable drugs with the potential to slow ageing and extend the healthspan are not being properly explored. Meanwhile, the people who need them most are growing old waiting.

- This article first appeared inissue 373ofBBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here

Read more about future medicine: